Chapter: 44

With Mahatma Gandhi at Wardha

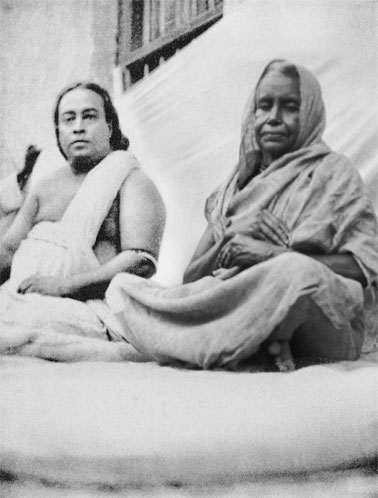

“Welcome to Wardha!” Mahadev Desai, secretary to Mahatma Gandhi, greeted Miss Bletch, Mr. Wright, and myself with these cordial words and the gift of wreaths of khaddar (homespun cotton). Our little group had just dismounted at the Wardha station on an early morning in August, glad to leave the dust and heat of the train. Consigning our luggage to a bullock cart, we entered an open motor car with Mr. Desai and his companions, Babasaheb Deshmukh and Dr. Pingale. A short drive over the muddy country roads brought us to Maganvadi, the ashram of India’s political saint.“Welcome!” he scribbled in Hindi; it was a Monday, his weekly day of silence.

Though this was our first meeting, we beamed on each other affectionately. In 1925 Mahatma Gandhi had honored the Ranchi school by a visit, and had inscribed in its guest-book a gracious tribute.

The tiny 100-pound saint radiated physical, mental, and spiritual health. His soft brown eyes shone with intelligence, sincerity, and discrimination; this statesman has matched wits and emerged the victor in a thousand legal, social, and political battles. No other leader in the world has attained the secure niche in the hearts of his people that Gandhi occupies for India’s unlettered millions. Their spontaneous tribute is his famous title—Mahatma, “great soul.” 1 For them alone Gandhi confines his attire to the widely-cartooned loincloth, symbol of his oneness with the downtrodden masses who can afford no more.

“The ashram residents are wholly at your disposal; please call on them for any service.” With characteristic courtesy, the Mahatma handed me this hastily-written note as Mr. Desai led our party from the writing room toward the guest house.

Our guide led us through orchards and flowering fields to a tile-roofed building with latticed windows. A front-yard well, twenty-five feet across, was used, Mr. Desai said, for watering stock; near-by stood a revolving cement wheel for threshing rice. Each of our small bedrooms proved to contain only the irreducible minimum—a bed, handmade of rope. The whitewashed kitchen boasted a faucet in one corner and a fire pit for cooking in another. Simple Arcadian sounds reached our ears—the cries of crows and sparrows, the lowing of cattle, and the rap of chisels being used to chip stones.

Observing Mr. Wright’s travel diary, Mr. Desai opened a page and wrote on it a list of Satyagraha 2 vows taken by all the Mahatma’s strict followers (satyagrahis):

“Nonviolence; Truth; Non-Stealing; Celibacy; Non-Possession; Body-Labor; Control of the Palate; Fearlessness; Equal Respect for all Religions; Swadeshi (use of home manufactures); Freedom from Untouchability. These eleven should be observed as vows in a spirit of humility.”(Gandhi himself signed this page on the following day, giving the date also—August 27, 1935.)

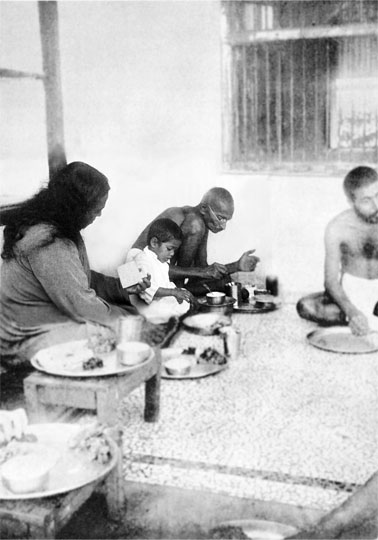

Two hours after our arrival my companions and I were summoned to lunch. The Mahatma was already seated under the arcade of the ashram porch, across the courtyard from his study. About twenty-five barefooted satyagrahis were squatting before brass cups and plates. A community chorus of prayer; then a meal served from large brass pots containing chapatis (whole-wheat unleavened bread) sprinkled with ghee; talsari (boiled and diced vegetables), and a lemon jam.

The Mahatma ate chapatis, boiled beets, some raw vegetables, and oranges. On the side of his plate was a large lump of very bitter neem leaves, a notable blood cleanser. With his spoon he separated a portion and placed it on my dish. I bolted it down with water, remembering childhood days when Mother had forced me to swallow the disagreeable dose. Gandhi, however, bit by bit was eating the neem paste with as much relish as if it had been a delicious sweetmeat.

In this trifling incident I noted the Mahatma’s ability to detach his mind from the senses at will. I recalled the famous appendectomy performed on him some years ago. Refusing anesthetics, the saint had chatted cheerfully with his disciples throughout the operation, his infectious smile revealing his unawareness of pain.

The afternoon brought an opportunity for a chat with Gandhi’s noted disciple, daughter of an English admiral, Miss Madeleine Slade, now called Mirabai.3 Her strong, calm face lit with enthusiasm as she told me, in flawless Hindi, of her daily activities.

“Rural reconstruction work is rewarding! A group of us go every morning at five o’clock to serve the near-by villagers and teach them simple hygiene. We make it a point to clean their latrines and their mud-thatched huts. The villagers are illiterate; they cannot be educated except by example!” She laughed gaily.

I looked in admiration at this highborn Englishwoman whose true Christian humility enables her to do the scavengering work usually performed only by “untouchables.”

“I came to India in 1925,” she told me. “In this land I feel that I have ‘come back home.’ Now I would never be willing to return to my old life and old interests.”

We discussed America for awhile. “I am always pleased and amazed,” she said, “to see the deep interest in spiritual subjects exhibited by the many Americans who visit India.” 4

Mirabai’s hands were soon busy at the charka (spinning wheel), omnipresent in all the ashram rooms and, indeed, due to the Mahatma, omnipresent throughout rural India.

Gandhi has sound economic and cultural reasons for encouraging the revival of cottage industries, but he does not counsel a fanatical repudiation of all modern progress. Machinery, trains, automobiles, the telegraph have played important parts in his own colossal life! Fifty years of public service, in prison and out, wrestling daily with practical details and harsh realities in the political world, have only increased his balance, open-mindedness, sanity, and humorous appreciation of the quaint human spectacle.

Our trio enjoyed a six o’clock supper as guests of Babasaheb Deshmukh. The 7:00 P.M. prayer hour found us back at the Maganvadi ashram, climbing to the roof where thirty satyagrahis were grouped in a semicircle around Gandhi. He was squatting on a straw mat, an ancient pocket watch propped up before him. The fading sun cast a last gleam over the palms and banyans; the hum of night and the crickets had started. The atmosphere was serenity itself; I was enraptured.

A solemn chant led by Mr. Desai, with responses from the group; then a Gita reading. The Mahatma motioned to me to give the concluding prayer. Such divine unison of thought and aspiration! A memory forever: the Wardha roof top meditation under the early stars.

Punctually at eight o’clock Gandhi ended his silence. The herculean labors of his life require him to apportion his time minutely.

“Welcome, Swamiji!” The Mahatma’s greeting this time was not via paper. We had just descended from the roof to his writing room, simply furnished with square mats (no chairs), a low desk with books, papers, and a few ordinary pens (not fountain pens); a nondescript clock ticked in a corner. An all-pervasive aura of peace and devotion. Gandhi was bestowing one of his captivating, cavernous, almost toothless smiles.

“Years ago,” he explained, “I started my weekly observance of a day of silence as a means for gaining time to look after my correspondence. But now those twenty-four hours have become a vital spiritual need. A periodical decree of silence is not a torture but a blessing.”

I agreed wholeheartedly.5 The Mahatma questioned me about America and Europe; we discussed India and world conditions.

“Mahadev,” Gandhi said as Mr. Desai entered the room, “please make arrangements at Town Hall for Swamiji to speak there on yoga tomorrow night.”

As I was bidding the Mahatma good night, he considerately handed me a bottle of citronella oil.

“The Wardha mosquitoes don’t know a thing about ahimsa,6 Swamiji!” he said, laughing.

The following morning our little group breakfasted early on a tasty wheat porridge with molasses and milk. At ten-thirty we were called to the ashram porch for lunch with Gandhi and the satyagrahis. Today the menu included brown rice, a new selection of vegetables, and cardamom seeds.

Noon found me strolling about the ashram grounds, on to the grazing land of a few imperturbable cows. The protection of cows is a passion with Gandhi.

“The cow to me means the entire sub-human world, extending man’s sympathies beyond his own species,” the Mahatma has explained. “Man through the cow is enjoined to realize his identity with all that lives. Why the ancient rishis selected the cow for apotheosis is obvious to me. The cow in India was the best comparison; she was the giver of plenty. Not only did she give milk, but she also made agriculture possible. The cow is a poem of pity; one reads pity in the gentle animal. She is the second mother to millions of mankind. Protection of the cow means protection of the whole dumb creation of God. The appeal of the lower order of creation is all the more forceful because it is speechless.”

Three daily rituals are enjoined on the orthodox Hindu. One is Bhuta Yajna, an offering of food to the animal kingdom. This ceremony symbolizes man’s realization of his obligations to less evolved forms of creation, instinctively tied to bodily identifications which also corrode human life, but lacking in that quality of liberating reason which is peculiar to humanity. Bhuta Yajna thus reinforces man’s readiness to succor the weak, as he in turn is comforted by countless solicitudes of higher unseen beings. Man is also under bond for rejuvenating gifts of nature, prodigal in earth, sea, and sky. The evolutionary barrier of incommunicability among nature, animals, man, and astral angels is thus overcome by offices of silent love.

The other two daily yajnas are Pitri and Nri. Pitri Yajna is an offering of oblations to ancestors, as a symbol of man’s acknowledgment of his debt to the past, essence of whose wisdom illumines humanity today. Nri Yajna is an offering of food to strangers or the poor, symbol of the present responsibilities of man, his duties to contemporaries.

In the early afternoon I fulfilled a neighborly Nri Yajna by a visit to Gandhi’s ashram for little girls. Mr. Wright accompanied me on the ten-minute drive. Tiny young flowerlike faces atop the long-stemmed colorful saris! At the end of a brief talk in Hindi 7 which I was giving outdoors, the skies unloosed a sudden downpour. Laughing, Mr. Wright and I climbed aboard the car and sped back to Maganvadi amidst sheets of driving silver. Such tropical intensity and splash!

Reentering the guest house I was struck anew by the stark simplicity and evidences of self-sacrifice which are everywhere present. The Gandhi vow of non-possession came early in his married life. Renouncing an extensive legal practice which had been yielding him an annual income of more than $20,000, the Mahatma dispersed all his wealth to the poor.

Sri Yukteswar used to poke gentle fun at the commonly inadequate conceptions of renunciation.

“A beggar cannot renounce wealth,” Master would say. “If a man laments: ‘My business has failed; my wife has left me; I will renounce all and enter a monastery,’ to what worldly sacrifice is he referring? He did not renounce wealth and love; they renounced him!”

Saints like Gandhi, on the other hand, have made not only tangible material sacrifices, but also the more difficult renunciation of selfish motive and private goal, merging their inmost being in the stream of humanity as a whole.

The Mahatma’s remarkable wife, Kasturabai, did not object when he failed to set aside any part of his wealth for the use of herself and their children. Married in early youth, Gandhi and his wife took the vow of celibacy after the birth of several sons.8 A tranquil heroine in the intense drama that has been their life together, Kasturabai has followed her husband to prison, shared his three-week fasts, and fully borne her share of his endless responsibilities. She has paid Gandhi the following tribute:

I thank you for having had the privilege of being your lifelong companion and helpmate. I thank you for the most perfect marriage in the world, based on brahmacharya (self-control) and not on sex. I thank you for having considered me your equal in your life work for India. I thank you for not being one of those husbands who spend their time in gambling, racing, women, wine, and song, tiring of their wives and children as the little boy quickly tires of his childhood toys. How thankful I am that you were not one of those husbands who devote their time to growing rich on the exploitation of the labor of others.For years Kasturabai performed the duties of treasurer of the public funds which the idolized Mahatma is able to raise by the millions. There are many humorous stories in Indian homes to the effect that husbands are nervous about their wives’ wearing any jewelry to a Gandhi meeting; the Mahatma’s magical tongue, pleading for the downtrodden, charms the gold bracelets and diamond necklaces right off the arms and necks of the wealthy into the collection basket!

How thankful I am that you put God and country before bribes, that you had the courage of your convictions and a complete and implicit faith in God. How thankful I am for a husband that put God and his country before me. I am grateful to you for your tolerance of me and my shortcomings of youth, when I grumbled and rebelled against the change you made in our mode of living, from so much to so little.

As a young child, I lived in your parents’ home; your mother was a great and good woman; she trained me, taught me how to be a brave, courageous wife and how to keep the love and respect of her son, my future husband. As the years passed and you became India’s most beloved leader, I had none of the fears that beset the wife who may be cast aside when her husband has climbed the ladder of success, as so often happens in other countries. I knew that death would still find us husband and wife.

One day the public treasurer, Kasturabai, could not account for a disbursement of four rupees. Gandhi duly published an auditing in which he inexorably pointed out his wife’s four rupee discrepancy.

I had often told this story before classes of my American students. One evening a woman in the hall had given an outraged gasp.

“Mahatma or no Mahatma,” she had cried, “if he were my husband I would have given him a black eye for such an unnecessary public insult!”

After some good-humored banter had passed between us on the subject of American wives and Hindu wives, I had gone on to a fuller explanation.

“Mrs. Gandhi considers the Mahatma not as her husband but as her guru, one who has the right to discipline her for even insignificant errors,” I had pointed out. “Sometime after Kasturabai had been publicly rebuked, Gandhi was sentenced to prison on a political charge. As he was calmly bidding farewell to his wife, she fell at his feet. ‘Master,’ she said humbly, ‘if I have ever offended you, please forgive me.’” 9

At three o’clock that afternoon in Wardha, I betook myself, by previous appointment, to the writing room of the saint who had been able to make an unflinching disciple out of his own wife—rare miracle! Gandhi looked up with his unforgettable smile.

“Mahatmaji,” I said as I squatted beside him on the uncushioned mat, “please tell me your definition of ahimsa.”

“The avoidance of harm to any living creature in thought or deed.”

“Beautiful ideal! But the world will always ask: May one not kill a cobra to protect a child, or one’s self?”

“I could not kill a cobra without violating two of my vows—fearlessness, and non-killing. I would rather try inwardly to calm the snake by vibrations of love. I cannot possibly lower my standards to suit my circumstances.” With his amazing candor, Gandhi added, “I must confess that I could not carry on this conversation were I faced by a cobra!”

I remarked on several very recent Western books on diet which lay on his desk.

“Yes, diet is important in the Satyagraha movement—as everywhere else,” he said with a chuckle. “Because I advocate complete continence for satyagrahis, I am always trying to find out the best diet for the celibate. One must conquer the palate before he can control the procreative instinct. Semi-starvation or unbalanced diets are not the answer. After overcoming the inward greed for food, a satyagrahi must continue to follow a rational vegetarian diet with all necessary vitamins, minerals, calories, and so forth. By inward and outward wisdom in regard to eating, the satyagrahi’s sexual fluid is easily turned into vital energy for the whole body.”

The Mahatma and I compared our knowledge of good meat-substitutes. “The avocado is excellent,” I said. “There are numerous avocado groves near my center in California.”

Gandhi’s face lit with interest. “I wonder if they would grow in Wardha? The satyagrahis would appreciate a new food.”

“I will be sure to send some avocado plants from Los Angeles to Wardha.” 10 I added, “Eggs are a high-protein food; are they forbidden to satyagrahis?”

“Not unfertilized eggs.” The Mahatma laughed reminiscently. “For years I would not countenance their use; even now I personally do not eat them. One of my daughters-in-law was once dying of malnutrition; her doctor insisted on eggs. I would not agree, and advised him to give her some egg-substitute.

“‘Gandhiji,’ the doctor said, ‘unfertilized eggs contain no life sperm; no killing is involved.’

“I then gladly gave permission for my daughter-in-law to eat eggs; she was soon restored to health.”

On the previous night Gandhi had expressed a wish to receive the Kriya Yoga of Lahiri Mahasaya. I was touched by the Mahatma’s open-mindedness and spirit of inquiry. He is childlike in his divine quest, revealing that pure receptivity which Jesus praised in children, “. . . of such is the kingdom of heaven.”

The hour for my promised instruction had arrived; several satyagrahis now entered the room—Mr. Desai, Dr. Pingale, and a few others who desired the Kriya technique.

I first taught the little class the physical Yogoda exercises. The body is visualized as divided into twenty parts; the will directs energy in turn to each section. Soon everyone was vibrating before me like a human motor. It was easy to observe the rippling effect on Gandhi’s twenty body parts, at all times completely exposed to view! Though very thin, he is not unpleasingly so; the skin of his body is smooth and unwrinkled.

Later I initiated the group into the liberating technique of Kriya Yoga.

The Mahatma has reverently studied all world religions. The Jain scriptures, the Biblical New Testament, and the sociological writings of Tolstoy 11 are the three main sources of Gandhi’s nonviolent convictions. He has stated his credo thus:

I believe the Bible, the Koran, and the Zend-Avesta 12 to be as divinely inspired as the Vedas. I believe in the institution of Gurus, but in this age millions must go without a Guru, because it is a rare thing to find a combination of perfect purity and perfect learning. But one need not despair of ever knowing the truth of one’s religion, because the fundamentals of Hinduism as of every great religion are unchangeable, and easily understood.Of Christ, Gandhi has written: “I am sure that if He were living here now among men, He would bless the lives of many who perhaps have never even heard His name . . . just as it is written: ‘Not every one that saith unto me, Lord, Lord . . . but he that doeth the will of my Father.’ 15 In the lesson of His own life, Jesus gave humanity the magnificent purpose and the single objective toward which we all ought to aspire. I believe that He belongs not solely to Christianity, but to the entire world, to all lands and races.”

I believe like every Hindu in God and His oneness, in rebirth and salvation. . . . I can no more describe my feeling for Hinduism than for my own wife. She moves me as no other woman in the world can. Not that she has no faults; I daresay she has many more than I see myself. But the feeling of an indissoluble bond is there. Even so I feel for and about Hinduism with all its faults and limitations. Nothing delights me so much as the music of the Gita, or the Ramayana by Tulsidas. When I fancied I was taking my last breath, the Gita was my solace.

Hinduism is not an exclusive religion. In it there is room for the worship of all the prophets of the world.13 It is not a missionary religion in the ordinary sense of the term. It has no doubt absorbed many tribes in its fold, but this absorption has been of an evolutionary, imperceptible character. Hinduism tells each man to worship God according to his own faith or dharma,14 and so lives at peace with all religions.

On my last evening in Wardha I addressed the meeting which had been called by Mr. Desai in Town Hall. The room was thronged to the window sills with about 400 people assembled to hear the talk on yoga. I spoke first in Hindi, then in English. Our little group returned to the ashram in time for a good-night glimpse of Gandhi, enfolded in peace and correspondence.

Night was still lingering when I rose at 5:00 A.M. Village life was already stirring; first a bullock cart by the ashram gates, then a peasant with his huge burden balanced precariously on his head. After breakfast our trio sought out Gandhi for farewell pronams. The saint rises at four o’clock for his morning prayer.

“Mahatmaji, good-by!” I knelt to touch his feet. “India is safe in your keeping!”

Years have rolled by since the Wardha idyl; the earth, oceans, and skies have darkened with a world at war. Alone among great leaders, Gandhi has offered a practical nonviolent alternative to armed might. To redress grievances and remove injustices, the Mahatma has employed nonviolent means which again and again have proved their effectiveness. He states his doctrine in these words:

I have found that life persists in the midst of destruction. Therefore there must be a higher law than that of destruction. Only under that law would well-ordered society be intelligible and life worth living.Consulting history, one may reasonably state that the problems of mankind have not been solved by the use of brute force. World War I produced a world-chilling snowball of war karma that swelled into World War II. Only the warmth of brotherhood can melt the present colossal snowball of war karma which may otherwise grow into World War III. This unholy trinity will banish forever the possibility of World War IV by a finality of atomic bombs. Use of jungle logic instead of human reason in settling disputes will restore the earth to a jungle. If brothers not in life, then brothers in violent death.

If that is the law of life we must work it out in daily existence. Wherever there are wars, wherever we are confronted with an opponent, conquer by love. I have found that the certain law of love has answered in my own life as the law of destruction has never done.

In India we have had an ocular demonstration of the operation of this law on the widest scale possible. I don’t claim that nonviolence has penetrated the 360,000,000 people in India, but I do claim it has penetrated deeper than any other doctrine in an incredibly short time.

It takes a fairly strenuous course of training to attain a mental state of nonviolence. It is a disciplined life, like the life of a soldier. The perfect state is reached only when the mind, body, and speech are in proper coordination. Every problem would lend itself to solution if we determined to make the law of truth and nonviolence the law of life.

Just as a scientist will work wonders out of various applications of the laws of nature, a man who applies the laws of love with scientific precision can work greater wonders. Nonviolence is infinitely more wonderful and subtle than forces of nature like, for instance, electricity. The law of love is a far greater science than any modern science.

War and crime never pay. The billions of dollars that went up in the smoke of explosive nothingness would have been sufficient to have made a new world, one almost free from disease and completely free from poverty. Not an earth of fear, chaos, famine, pestilence, the danse macabre, but one broad land of peace, of prosperity, and of widening knowledge.

The nonviolent voice of Gandhi appeals to man’s highest conscience. Let nations ally themselves no longer with death, but with life; not with destruction, but with construction; not with the Annihilator, but with the Creator.

“One should forgive, under any injury,” says the Mahabharata. “It hath been said that the continuation of species is due to man’s being forgiving. Forgiveness is holiness; by forgiveness the universe is held together. Forgiveness is the might of the mighty; forgiveness is sacrifice; forgiveness is quiet of mind. Forgiveness and gentleness are the qualities of the self-possessed. They represent eternal virtue.”

Nonviolence is the natural outgrowth of the law of forgiveness and love. “If loss of life becomes necessary in a righteous battle,” Gandhi proclaims, “one should be prepared, like Jesus, to shed his own, not others’, blood. Eventually there will be less blood spilt in the world.”

Epics shall someday be written on the Indian satyagrahis who withstood hate with love, violence with nonviolence, who allowed themselves to be mercilessly slaughtered rather than retaliate. The result on certain historic occasions was that the armed opponents threw down their guns and fled, shamed, shaken to their depths by the sight of men who valued the life of another above their own.

“I would wait, if need be for ages,” Gandhi says, “rather than seek the freedom of my country through bloody means.” Never does the Mahatma forget the majestic warning: “All they that take the sword shall perish with the sword.” 16 Gandhi has written:

I call myself a nationalist, but my nationalism is as broad as the universe. It includes in its sweep all the nations of the earth.17 My nationalism includes the well-being of the whole world. I do not want my India to rise on the ashes of other nations. I do not want India to exploit a single human being. I want India to be strong in order that she can infect the other nations also with her strength. Not so with a single nation in Europe today; they do not give strength to the others.By the Mahatma’s training of thousands of true satyagrahis (those who have taken the eleven rigorous vows mentioned in the first part of this chapter), who in turn spread the message; by patiently educating the Indian masses to understand the spiritual and eventually material benefits of nonviolence; by arming his people with nonviolent weapons—non-cooperation with injustice, the willingness to endure indignities, prison, death itself rather than resort to arms; by enlisting world sympathy through countless examples of heroic martyrdom among satyagrahis, Gandhi has dramatically portrayed the practical nature of nonviolence, its solemn power to settle disputes without war.

President Wilson mentioned his beautiful fourteen points, but said: “After all, if this endeavor of ours to arrive at peace fails, we have our armaments to fall back upon.” I want to reverse that position, and I say: “Our armaments have failed already. Let us now be in search of something new; let us try the force of love and God which is truth.” When we have got that, we shall want nothing else.

Gandhi has already won through nonviolent means a greater number of political concessions for his land than have ever been won by any leader of any country except through bullets. Nonviolent methods for eradication of all wrongs and evils have been strikingly applied not only in the political arena but in the delicate and complicated field of Indian social reform. Gandhi and his followers have removed many longstanding feuds between Hindus and Mohammedans; hundreds of thousands of Moslems look to the Mahatma as their leader. The untouchables have found in him their fearless and triumphant champion. “If there be a rebirth in store for me,” Gandhi wrote, “I wish to be born a pariah in the midst of pariahs, because thereby I would be able to render them more effective service.”

The Mahatma is indeed a “great soul,” but it was illiterate millions who had the discernment to bestow the title. This gentle prophet is honored in his own land. The lowly peasant has been able to rise to Gandhi’s high challenge. The Mahatma wholeheartedly believes in the inherent nobility of man. The inevitable failures have never disillusioned him. “Even if the opponent plays him false twenty times,” he writes, “the satyagrahi is ready to trust him the twenty-first time, for an implicit trust in human nature is the very essence of the creed.” 18

“Mahatmaji, you are an exceptional man. You must not expect the world to act as you do.” A critic once made this observation.

“It is curious how we delude ourselves, fancying that the body can be improved, but that it is impossible to evoke the hidden powers of the soul,” Gandhi replied. “I am engaged in trying to show that if I have any of those powers, I am as frail a mortal as any of us and that I never had anything extraordinary about me nor have I now. I am a simple individual liable to err like any other fellow mortal. I own, however, that I have enough humility to confess my errors and to retrace my steps. I own that I have an immovable faith in God and His goodness, and an unconsumable passion for truth and love. But is that not what every person has latent in him? If we are to make progress, we must not repeat history but make new history. We must add to the inheritance left by our ancestors. If we may make new discoveries and inventions in the phenomenal world, must we declare our bankruptcy in the spiritual domain? Is it impossible to multiply the exceptions so as to make them the rule? Must man always be brute first and man after, if at all?” 19

Americans may well remember with pride the successful nonviolent experiment of William Penn in founding his 17th century colony in Pennsylvania. There were “no forts, no soldiers, no militia, even no arms.” Amidst the savage frontier wars and the butcheries that went on between the new settlers and the Red Indians, the Quakers of Pennsylvania alone remained unmolested. “Others were slain; others were massacred; but they were safe. Not a Quaker woman suffered assault; not a Quaker child was slain, not a Quaker man was tortured.” When the Quakers were finally forced to give up the government of the state, “war broke out, and some Pennsylvanians were killed. But only three Quakers were killed, three who had so far fallen from their faith as to carry weapons of defence.”

“Resort to force in the Great War (I) failed to bring tranquillity,” Franklin D. Roosevelt has pointed out. “Victory and defeat were alike sterile. That lesson the world should have learned.”

“The more weapons of violence, the more misery to mankind,” Lao-tzu taught. “The triumph of violence ends in a festival of mourning.”

“I am fighting for nothing less than world peace,” Gandhi has declared. “If the Indian movement is carried to success on a nonviolent Satyagraha basis, it will give a new meaning to patriotism and, if I may say so in all humility, to life itself.”

Before the West dismisses Gandhi’s program as one of an impractical dreamer, let it first reflect on a definition of Satyagraha by the Master of Galilee:

“Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: but I say unto you, That ye resist not evil:20 but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also.”

Gandhi’s epoch has extended, with the beautiful precision of cosmic timing, into a century already desolated and devastated by two World Wars. A divine handwriting appears on the granite wall of his life: a warning against the further shedding of blood among brothers.

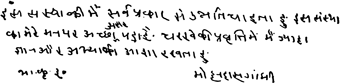

Mahatma Gandhi’s Handwriting in HindiMahatma Gandhi visited my high school with yoga training at Ranchi. He graciously wrote the above lines in the Ranchi guest-book. The translation is:

“This institution has deeply impressed my mind. I cherish high hopes that this school will encourage the further practical use of the spinning wheel.”

( Signed ) MOHANDAS GANDHISeptember 17, 1925

A national flag for India was designed in 1921 by Gandhi. The stripes are saffron, white and green; the charka ( spinning wheel ) in the center is dark blue.

“The charka symbolizes energy,” he wrote, “and reminds us that during the past eras of prosperity in India’s history, hand spinning and other domestic crafts were prominent.”

-

His family name is Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He never refers to himself as “Mahatma.”▲

-

The literal translation from Sanskrit is “holding to truth.” Satyagraha is the famous nonviolence movement led by Gandhi.▲

-

False and alas! malicious reports were recently circulated

that Miss Slade has severed all her ties with Gandhi and forsaken her

vows. Miss Slade, the Mahatma’s Satyagraha disciple for twenty years, issued a signed statement to the United Press,

dated Dec. 29, 1945, in which she explained that a series of baseless

rumors arose after she had departed, with Gandhi’s blessings, for a

small site in northeastern India near the Himalayas, for the purpose of

founding there her now-flourishing Kisan Ashram (center for medical and agricultural aid to peasant farmers). Mahatma Gandhi plans to visit the new ashram during 1946.▲

-

Miss Slade reminded me of another distinguished Western

woman, Miss Margaret Woodrow Wilson, eldest daughter of America’s great

president. I met her in New York; she was intensely interested in India.

Later she went to Pondicherry, where she spent the last five years of

her life, happily pursuing a path of discipline at the feet of Sri

Aurobindo Ghosh. This sage never speaks; he silently greets his

disciples on three annual occasions only.▲

-

For years in America I had been observing periods of silence, to the consternation of callers and secretaries.▲

-

Harmlessness; nonviolence; the foundation rock of Gandhi’s creed. He was born into a family of strict Jains, who revere ahimsa

as the root-virtue. Jainism, a sect of Hinduism, was founded in the 6th

century B.C. by Mahavira, a contemporary of Buddha. Mahavira means

“great hero”; may he look down the centuries on his heroic son Gandhi!▲

-

Hindi is the lingua franca for the whole of India. An

Indo-Aryan language based largely on Sanskrit roots, Hindi is the chief

vernacular of northern India. The main dialect of Western Hindi is

Hindustani, written both in the Devanagari (Sanskrit) characters and in Arabic characters. Its subdialect, Urdu, is spoken by Moslems.▲

-

Gandhi has described his life with a devastating candor in The Story of my Experiments with Truth (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Press, 1927-29, 2 vol.) This autobiography has been summarized in Mahatma Gandhi, His Own Story, edited by C. F. Andrews, with an introduction by John Haynes Holmes (New York: Macmillan Co., 1930).

Many autobiographies replete with famous names and colorful events are almost completely silent on any phase of inner analysis or development. One lays down each of these books with a certain dissatisfaction, as though saying: “Here is a man who knew many notable persons, but who never knew himself.” This reaction is impossible with Gandhi’s autobiography; he exposes his faults and subterfuges with an impersonal devotion to truth rare in annals of any age.▲

-

Kasturabai Gandhi died in imprisonment at Poona on February

22, 1944. The usually unemotional Gandhi wept silently. Shortly after

her admirers had suggested a Memorial Fund in her honor, 125 lacs of

rupees (nearly four million dollars) poured in from all over India.

Gandhi has arranged that the fund be used for village welfare work among

women and children. He reports his activities in his English weekly, Harijan.▲

-

I sent a shipment to Wardha, soon after my return to America.

The plants, alas! died on the way, unable to withstand the rigors of

the long ocean transportation.▲

-

Thoreau, Ruskin, and Mazzini are three other Western writers whose sociological views Gandhi has studied carefully.▲

-

The sacred scripture given to Persia about 1000 B.C. by Zoroaster.▲

-

The unique feature of Hinduism among the world religions is

that it derives not from a single great founder but from the impersonal

Vedic scriptures. Hinduism thus gives scope for worshipful incorporation

into its fold of prophets of all ages and all lands. The Vedic

scriptures regulate not only devotional practices but all important

social customs, in an effort to bring man’s every action into harmony

with divine law.▲

-

A comprehensive Sanskrit word for law; conformity to law or

natural righteousness; duty as inherent in the circumstances in which a

man finds himself at any given time. The scriptures define dharma as “the natural universal laws whose observance enables man to save himself from degradation and suffering.”▲

-

Matthew 7:21.▲

-

Matthew 26:52.▲

-

“Let not a man glory in this, that he love his country; Let him rather glory in this, that he love his kind.”—Persian Proverb.▲

-

“Then came Peter to him and said, Lord, how oft shall my

brother sin against me, and I forgive him? till seven times? Jesus saith

unto him, I say not unto thee, Until seven times: but, Until seventy

times seven.”—Matthew 18:21-22.▲

-

Charles P. Steinmetz, the great electrical engineer, was once

asked by Mr. Roger W. Babson: “What line of research will see the

greatest development during the next fifty years?” “I think the greatest

discovery will be made along spiritual lines,” Steinmetz replied. “Here

is a force which history clearly teaches has been the greatest power in

the development of men. Yet we have merely been playing with it and

have never seriously studied it as we have the physical forces. Someday

people will learn that material things do not bring happiness and are of

little use in making men and women creative and powerful. Then the

scientists of the world will turn their laboratories over to the study

of God and prayer and the spiritual forces which as yet have hardly been

scratched. When this day comes, the world will see more advancement in

one generation than it has seen in the past four.”▲

-

That is, resist not evil with evil. (Matthew 5:38-39)▲

Chapter: 45

The Bengali “Joy-Permeated Mother”

“Sir, please do not leave India without a glimpse of Nirmala Devi. Her sanctity is intense; she is known far and wide as Ananda Moyi Ma (Joy-Permeated Mother).” My niece, Amiyo Bose, gazed at me earnestly.“Of course! I want very much to see the woman saint.” I added, “I have read of her advanced state of God-realization. A little article about her appeared years ago in East-West.”

“I have met her,” Amiyo went on. “She recently visited my own little town of Jamshedpur. At the entreaty of a disciple, Ananda Moyi Ma went to the home of a dying man. She stood by his bedside; as her hand touched his forehead, his death-rattle ceased. The disease vanished at once; to the man’s glad astonishment, he was well.”

A few days later I heard that the Blissful Mother was staying at the home of a disciple in the Bhowanipur section of Calcutta. Mr. Wright and I set out immediately from my father’s Calcutta home. As the Ford neared the Bhowanipur house, my companion and I observed an unusual street scene.

Ananda Moyi Ma was standing in an open-topped automobile, blessing a throng of about one hundred disciples. She was evidently on the point of departure. Mr. Wright parked the Ford some distance away, and accompanied me on foot toward the quiet assemblage. The woman saint glanced in our direction; she alit from her car and walked toward us.

“Father, you have come!” With these fervent words she put her arm around my neck and her head on my shoulder. Mr. Wright, to whom I had just remarked that I did not know the saint, was hugely enjoying this extraordinary demonstration of welcome. The eyes of the one hundred chelas were also fixed with some surprise on the affectionate tableau.

I had instantly seen that the saint was in a high state of samadhi. Utterly oblivious to her outward garb as a woman, she knew herself as the changeless soul; from that plane she was joyously greeting another devotee of God. She led me by the hand into her automobile.

“Ananda Moyi Ma, I am delaying your journey!” I protested.

“Father, I am meeting you for the first time in this life, after ages!” she said. “Please do not leave yet.”

We sat together in the rear seats of the car. The Blissful Mother soon entered the immobile ecstatic state. Her beautiful eyes glanced heavenward and, half-opened, became stilled, gazing into the near-far inner Elysium. The disciples chanted gently: “Victory to Mother Divine!”

I had found many men of God-realization in India, but never before had I met such an exalted woman saint. Her gentle face was burnished with the ineffable joy that had given her the name of Blissful Mother. Long black tresses lay loosely behind her unveiled head. A red dot of sandalwood paste on her forehead symbolized the spiritual eye, ever open within her. Tiny face, tiny hands, tiny feet—a contrast to her spiritual magnitude!

I put some questions to a near-by woman chela while Ananda Moyi Ma remained entranced.

“The Blissful Mother travels widely in India; in many parts she has hundreds of disciples,” the chela told me. “Her courageous efforts have brought about many desirable social reforms. Although a Brahmin, the saint recognizes no caste distinctions.1 A group of us always travel with her, looking after her comforts. We have to mother her; she takes no notice of her body. If no one gave her food, she would not eat, or make any inquiries. Even when meals are placed before her, she does not touch them. To prevent her disappearance from this world, we disciples feed her with our own hands. For days together she often stays in the divine trance, scarcely breathing, her eyes unwinking. One of her chief disciples is her husband. Many years ago, soon after their marriage, he took the vow of silence.”

The chela pointed to a broad-shouldered, fine-featured man with long hair and hoary beard. He was standing quietly in the midst of the gathering, his hands folded in a disciple’s reverential attitude.

Refreshed by her dip in the Infinite, Ananda Moyi Ma was now focusing her consciousness on the material world.

“Father, please tell me where you stay.” Her voice was clear and melodious.

“At present, in Calcutta or Ranchi; but soon I shall be returning to America.”

“America?”

“Yes. An Indian woman saint would be sincerely appreciated there by spiritual seekers. Would you like to go?”

“If Father can take me, I will go.”

This reply caused her near-by disciples to start in alarm.

“Twenty or more of us always travel with the Blissful Mother,” one of them told me firmly. “We could not live without her. Wherever she goes, we must go.”

Reluctantly I abandoned the plan, as possessing an impractical feature of spontaneous enlargement!

“Please come at least to Ranchi, with your disciples,” I said on taking leave of the saint. “As a divine child yourself, you will enjoy the little ones in my school.”

“Whenever Father takes me, I will gladly go.”

A short time later the Ranchi Vidyalaya was in gala array for the saint’s promised visit. The youngsters looked forward to any day of festivity—no lessons, hours of music, and a feast for the climax!

“Victory! Ananda Moyi Ma, ki jai!” This reiterated chant from scores of enthusiastic little throats greeted the saint’s party as it entered the school gates. Showers of marigolds, tinkle of cymbals, lusty blowing of conch shells and beat of the mridanga drum! The Blissful Mother wandered smilingly over the sunny Vidyalaya grounds, ever carrying within her the portable paradise.

“It is beautiful here,” Ananda Moyi Ma said graciously as I led her into the main building. She seated herself with a childlike smile by my side. The closest of dear friends, she made one feel, yet an aura of remoteness was ever around her—the paradoxical isolation of Omnipresence.

“Please tell me something of your life.”

“Father knows all about it; why repeat it?” She evidently felt that the factual history of one short incarnation was beneath notice.

I laughed, gently repeating my question.

“Father, there is little to tell.” She spread her graceful hands in a deprecatory gesture. “My consciousness has never associated itself with this temporary body. Before I came on this earth, Father, ‘I was the same.’ As a little girl, ‘I was the same.’ I grew into womanhood, but still ‘I was the same.’ When the family in which I had been born made arrangements to have this body married, ‘I was the same.’ And when, passion-drunk, my husband came to me and murmured endearing words, lightly touching my body, he received a violent shock, as if struck by lightning, for even then ‘I was the same.’

“My husband knelt before me, folded his hands, and implored my pardon.

“‘Mother,’ he said, ‘because I have desecrated your bodily temple by touching it with the thought of lust—not knowing that within it dwelt not my wife but the Divine Mother—I take this solemn vow: I shall be your disciple, a celibate follower, ever caring for you in silence as a servant, never speaking to anyone again as long as I live. May I thus atone for the sin I have today committed against you, my guru.’

“Even when I quietly accepted this proposal of my husband’s, ‘I was the same.’ And, Father, in front of you now, ‘I am the same.’ Ever afterward, though the dance of creation change around me in the hall of eternity, ‘I shall be the same.’”

Ananda Moyi Ma sank into a deep meditative state. Her form was statue-still; she had fled to her ever-calling kingdom. The dark pools of her eyes appeared lifeless and glassy. This expression is often present when saints remove their consciousness from the physical body, which is then hardly more than a piece of soulless clay. We sat together for an hour in the ecstatic trance. She returned to this world with a gay little laugh.

“Please, Ananda Moyi Ma,” I said, “come with me to the garden. Mr. Wright will take some pictures.”

“Of course, Father. Your will is my will.” Her glorious eyes retained the unchanging divine luster as she posed for many photographs.

Time for the feast! Ananda Moyi Ma squatted on her blanket-seat, a disciple at her elbow to feed her. Like an infant, the saint obediently swallowed the food after the chela had brought it to her lips. It was plain that the Blissful Mother did not recognize any difference between curries and sweetmeats!

As dusk approached, the saint left with her party amidst a shower of rose petals, her hands raised in blessing on the little lads. Their faces shone with the affection she had effortlessly awakened.

“Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength:” Christ has proclaimed, “this is the first commandment.” 2

Casting aside every inferior attachment, Ananda Moyi Ma offers her sole allegiance to the Lord. Not by the hairsplitting distinctions of scholars but by the sure logic of faith, the childlike saint has solved the only problem in human life—establishment of unity with God. Man has forgotten this stark simplicity, now befogged by a million issues. Refusing a monotheistic love to God, the nations disguise their infidelity by punctilious respect before the outward shrines of charity. These humanitarian gestures are virtuous, because for a moment they divert man’s attention from himself, but they do not free him from his single responsibility in life, referred to by Jesus as the first commandment. The uplifting obligation to love God is assumed with man’s first breath of an air freely bestowed by his only Benefactor.

On one other occasion after her Ranchi visit I had opportunity to see Ananda Moyi Ma. She stood among her disciples some months later on the Serampore station platform, waiting for the train.

“Father, I am going to the Himalayas,” she told me. “Generous disciples have built me a hermitage in Dehra Dun.”

As she boarded the train, I marveled to see that whether amidst a crowd, on a train, feasting, or sitting in silence, her eyes never looked away from God. Within me I still hear her voice, an echo of measureless sweetness:

“Behold, now and always one with the Eternal, ‘I am ever the same.’”

-

I find some further facts of Ananda Moyi Ma’s life, printed in East-West.

The saint was born in 1893 at Dacca in central Bengal. Illiterate, she

has yet stunned the intellectuals by her wisdom. Her verses in Sanskrit

have filled scholars with wonderment. She has brought consolation to

bereaved persons, and effected miraculous cures, by her mere presence.▲

-

Mark 12:30.▲

Chapter: 46

The Woman Yogi Who Never Eats

“Sir, whither are we bound this morning?” Mr. Wright was driving the Ford; he took his eyes off the road long enough to gaze at me with a questioning twinkle. From day to day he seldom knew what part of Bengal he would be discovering next.“God willing,” I replied devoutly, “we are on our way to see an eighth wonder of the world—a woman saint whose diet is thin air!”

“Repetition of wonders—after Therese Neumann.” But Mr. Wright laughed eagerly just the same; he even accelerated the speed of the car. More extraordinary grist for his travel diary! Not one of an average tourist, that!

The Ranchi school had just been left behind us; we had risen before the sun. Besides my secretary and myself, three Bengali friends were in the party. We drank in the exhilarating air, the natural wine of the morning. Our driver guided the car warily among the early peasants and the two-wheeled carts, slowly drawn by yoked, hump-shouldered bullocks, inclined to dispute the road with a honking interloper.

“Sir, we would like to know more of the fasting saint.”

“Her name is Giri Bala,” I informed my companions. “I first heard about her years ago from a scholarly gentleman, Sthiti Lal Nundy. He often came to the Gurpar Road home to tutor my brother Bishnu.”

“‘I know Giri Bala well,’ Sthiti Babu told me. ‘She employs a certain yoga technique which enables her to live without eating. I was her close neighbor in Nawabganj near Ichapur.1 I made it a point to watch her closely; never did I find evidence that she was taking either food or drink. My interest finally mounted so high that I approached the Maharaja of Burdwan 2 and asked him to conduct an investigation. Astounded at the story, he invited her to his palace. She agreed to a test and lived for two months locked up in a small section of his home. Later she returned for a palace visit of twenty days; and then for a third test of fifteen days. The Maharaja himself told me that these three rigorous scrutinies had convinced him beyond doubt of her non-eating state.’

Giri Bala

This great woman yogi has not

taken food or drink since 1880. I am pictured with her, in 1936, at her

home in the isolated Bengal village of Biur. Her non-eating state has

been rigorously investigated by the Maharaja of Burdwan. She employs a

certain yoga technique to recharge her body with cosmic energy from the

ether, sun, and air.

By ten-thirty our little group was conversing with the brother, Lambadar Dey, a lawyer of Purulia.

“Yes, my sister is living. She sometimes stays with me here, but at present she is at our family home in Biur.” Lambadar Babu glanced doubtfully at the Ford. “I hardly think, Swamiji, that any automobile has ever penetrated into the interior as far as Biur. It might be best if you all resign yourselves to the ancient jolt of the bullock cart!”

As one voice our party pledged loyalty to the Pride of Detroit.

“The Ford comes from America,” I told the lawyer. “It would be a shame to deprive it of an opportunity to get acquainted with the heart of Bengal!”

“May Ganesh 4 go with you!” Lambadar Babu said, laughing. He added courteously, “If you ever get there, I am sure Giri Bala will be glad to see you. She is approaching her seventies, but continues in excellent health.”

“Please tell me, sir, if it is absolutely true that she eats nothing?” I looked directly into his eyes, those telltale windows of the mind.

“It is true.” His gaze was open and honorable. “In more than five decades I have never seen her eat a morsel. If the world suddenly came to an end, I could not be more astonished than by the sight of my sister’s taking food!”

We chuckled together over the improbability of these two cosmic events.

“Giri Bala has never sought an inaccessible solitude for her yoga practices,” Lambadar Babu went on. “She has lived her entire life surrounded by her family and friends. They are all well accustomed now to her strange state. Not one of them who would not be stupefied if Giri Bala suddenly decided to eat anything! Sister is naturally retiring, as befits a Hindu widow, but our little circle in Purulia and in Biur all know that she is literally an ‘exceptional’ woman.”

The brother’s sincerity was manifest. Our little party thanked him warmly and set out toward Biur. We stopped at a street shop for curry and luchis, attracting a swarm of urchins who gathered round to watch Mr. Wright eating with his fingers in the simple Hindu manner.5 Hearty appetites caused us to fortify ourselves against an afternoon which, unknown at the moment, was to prove fairly laborious.

Our way now led east through sun-baked rice fields into the Burdwan section of Bengal. On through roads lined with dense vegetation; the songs of the maynas and the stripe-throated bulbuls streamed out from trees with huge, umbrellalike branches. A bullock cart now and then, the rini, rini, manju, manju squeak of its axle and iron-shod wooden wheels contrasting sharply in mind with the swish, swish of auto tires over the aristocratic asphalt of the cities.

“Dick, halt!” My sudden request brought a jolting protest from the Ford. “That overburdened mango tree is fairly shouting an invitation!”

The five of us dashed like children to the mango-strewn earth; the tree had benevolently shed its fruits as they had ripened.

“Full many a mango is born to lie unseen,” I paraphrased, “and waste its sweetness on the stony ground.”

“Nothing like this in America, Swamiji, eh?” laughed Sailesh Mazumdar, one of my Bengali students.

“No,” I admitted, covered with mango juice and contentment. “How I have missed this fruit in the West! A Hindu’s heaven without mangoes is inconceivable!”

I picked up a rock and downed a proud beauty hidden on the highest limb.

“Dick,” I asked between bites of ambrosia, warm with the tropical sun, “are all the cameras in the car?”

“Yes, sir; in the baggage compartment.”

“If Giri Bala proves to be a true saint, I want to write about her in the West. A Hindu yogini with such inspiring powers should not live and die unknown—like most of these mangoes.”

Half an hour later I was still strolling in the sylvan peace.

“Sir,” Mr. Wright remarked, “we should reach Giri Bala before the sun sets, to have enough light for photographs.” He added with a grin, “The Westerners are a skeptical lot; we can’t expect them to believe in the lady without any pictures!”

This bit of wisdom was indisputable; I turned my back on temptation and reentered the car.

“You are right, Dick,” I sighed as we sped along, “I sacrifice the mango paradise on the altar of Western realism. Photographs we must have!”

The road became more and more sickly: wrinkles of ruts, boils of hardened clay, the sad infirmities of old age! Our group dismounted occasionally to allow Mr. Wright to more easily maneuver the Ford, which the four of us pushed from behind.

“Lambadar Babu spoke truly,” Sailesh acknowledged. “The car is not carrying us; we are carrying the car!”

Our climb-in, climb-out auto tedium was beguiled ever and anon by the appearance of a village, each one a scene of quaint simplicity.

“Our way twisted and turned through groves of palms among ancient, unspoiled villages nestling in the forest shade,” Mr. Wright has recorded in his travel diary, under date of May 5, 1936. “Very fascinating are these clusters of thatched mud huts, decorated with one of the names of God on the door; many small, naked children innocently playing about, pausing to stare or run wildly from this big, black, bullockless carriage tearing madly through their village. The women merely peep from the shadows, while the men lazily loll beneath the trees along the roadside, curious beneath their nonchalance. In one place, all the villagers were gaily bathing in the large tank (in their garments, changing by draping dry cloths around their bodies, dropping the wet ones). Women bearing water to their homes, in huge brass jars.Mr. Wright’s impression of Giri Bala was shared by myself; spirituality enfolded her like her gently shining veil. She pronamed before me in the customary gesture of greeting from a householder to a monk. Her simple charm and quiet smile gave us a welcome beyond that of honeyed oratory; forgotten was our difficult, dusty trip.

“The road led us a merry chase over mount and ridge; we bounced and tossed, dipped into small streams, detoured around an unfinished causeway, slithered across dry, sandy river beds and finally, about 5:00 P.M., we were close to our destination, Biur. This minute village in the interior of Bankura District, hidden in the protection of dense foliage, is unapproachable by travelers during the rainy season, when the streams are raging torrents and the roads serpentlike spit the mud-venom.

“Asking for a guide among a group of worshipers on their way home from a temple prayer (out in the lonely field), we were besieged by a dozen scantily clad lads who clambered on the sides of the car, eager to conduct us to Giri Bala.

“The road led toward a grove of date palms sheltering a group of mud huts, but before we had reached it, the Ford was momentarily tipped at a dangerous angle, tossed up and dropped down. The narrow trail led around trees and tank, over ridges, into holes and deep ruts. The car became anchored on a clump of bushes, then grounded on a hillock, requiring a lift of earth clods; on we proceeded, slowly and carefully; suddenly the way was stopped by a mass of brush in the middle of the cart track, necessitating a detour down a precipitous ledge into a dry tank, rescue from which demanded some scraping, adzing, and shoveling. Again and again the road seemed impassable, but the pilgrimage must go on; obliging lads fetched spades and demolished the obstacles (shades of Ganesh!) while hundreds of children and parents stared.

“Soon we were threading our way along the two ruts of antiquity, women gazing wide-eyed from their hut doors, men trailing alongside and behind us, children scampering to swell the procession. Ours was perhaps the first auto to traverse these roads; the ‘bullock cart union’ must be omnipotent here! What a sensation we created—a group piloted by an American and pioneering in a snorting car right into their hamlet fastness, invading the ancient privacy and sanctity!

“Halting by a narrow lane we found ourselves within a hundred feet of Giri Bala’s ancestral home. We felt the thrill of fulfillment after the long road struggle crowned by a rough finish. We approached a large, two-storied building of brick and plaster, dominating the surrounding adobe huts; the house was under the process of repair, for around it was the characteristically tropical framework of bamboos.

“With feverish anticipation and suppressed rejoicing we stood before the open doors of the one blessed by the Lord’s ‘hungerless’ touch. Constantly agape were the villagers, young and old, bare and dressed, women aloof somewhat but inquisitive too, men and boys unabashedly at our heels as they gazed on this unprecedented spectacle.

“Soon a short figure came into view in the doorway—Giri Bala! She was swathed in a cloth of dull, goldish silk; in typically Indian fashion, she drew forward modestly and hesitatingly, peering slightly from beneath the upper fold of her swadeshi cloth. Her eyes glistened like smouldering embers in the shadow of her head piece; we were enamored by a most benevolent and kindly face, a face of realization and understanding, free from the taint of earthly attachment.

“Meekly she approached and silently assented to our snapping a number of pictures with our ‘still’ and ‘movie’ cameras.6 Patiently and shyly she endured our photo techniques of posture adjustment and light arrangement. Finally we had recorded for posterity many photographs of the only woman in the world who is known to have lived without food or drink for over fifty years. (Therese Neumann, of course, has fasted since 1923.) Most motherly was Giri Bala’s expression as she stood before us, completely covered in the loose-flowing cloth, nothing of her body visible but her face with its downcast eyes, her hands, and her tiny feet. A face of rare peace and innocent poise—a wide, childlike, quivering lip, a feminine nose, narrow, sparkling eyes, and a wistful smile.”

The little saint seated herself cross-legged on the verandah. Though bearing the scars of age, she was not emaciated; her olive-colored skin had remained clear and healthy in tone.

“Mother,” I said in Bengali, “for over twenty-five years I have thought eagerly of this very pilgrimage! I heard about your sacred life from Sthiti Lal Nundy Babu.”

She nodded in acknowledgment. “Yes, my good neighbor in Nawabganj.”

“During those years I have crossed the oceans, but I never forgot my early plan to someday see you. The sublime drama that you are here playing so inconspicuously should be blazoned before a world that has long forgotten the inner food divine.”

The saint lifted her eyes for a minute, smiling with serene interest.

“Baba (honored father) knows best,” she answered meekly.

I was happy that she had taken no offense; one never knows how great yogis or yoginis will react to the thought of publicity. They shun it, as a rule, wishing to pursue in silence the profound soul research. An inner sanction comes to them when the proper time arrives to display their lives openly for the benefit of seeking minds.

“Mother,” I went on, “please forgive me, then, for burdening you with many questions. Kindly answer only those that please you; I shall understand your silence, also.”

She spread her hands in a gracious gesture. “I am glad to reply, insofar as an insignificant person like myself can give satisfactory answers.”

“Oh, no, not insignificant!” I protested sincerely. “You are a great soul.”

“I am the humble servant of all.” She added quaintly, “I love to cook and feed people.”

A strange pastime, I thought, for a non-eating saint!

“Tell me, Mother, from your own lips—do you live without food?”

“That is true.” She was silent for a few moments; her next remark showed that she had been struggling with mental arithmetic. “From the age of twelve years four months down to my present age of sixty-eight—a period of over fifty-six years—I have not eaten food or taken liquids.”

“Are you never tempted to eat?”

“If I felt a craving for food, I would have to eat.” Simply yet regally she stated this axiomatic truth, one known too well by a world revolving around three meals a day!

“But you do eat something!” My tone held a note of remonstrance.

“Of course!” She smiled in swift understanding.

“Your nourishment derives from the finer energies of the air and sunlight,7 and from the cosmic power which recharges your body through the medulla oblongata.”

“Baba knows.” Again she acquiesced, her manner soothing and unemphatic.

“Mother, please tell me about your early life. It holds a deep interest for all of India, and even for our brothers and sisters beyond the seas.”

Giri Bala put aside her habitual reserve, relaxing into a conversational mood.

“So be it.” Her voice was low and firm. “I was born in these forest regions. My childhood was unremarkable save that I was possessed by an insatiable appetite. I had been betrothed in early years.

“‘Child,’ my mother often warned me, ‘try to control your greed. When the time comes for you to live among strangers in your husband’s family, what will they think of you if your days are spent in nothing but eating?’

“The calamity she had foreseen came to pass. I was only twelve when I joined my husband’s people in Nawabganj. My mother-in-law shamed me morning, noon, and night about my gluttonous habits. Her scoldings were a blessing in disguise, however; they roused my dormant spiritual tendencies. One morning her ridicule was merciless.

“‘I shall soon prove to you,’ I said, stung to the quick, ‘that I shall never touch food again as long as I live.’

“My mother-in-law laughed in derision. ‘So!’ she said, ‘how can you live without eating, when you cannot live without overeating?’

“This remark was unanswerable! Yet an iron resolution scaffolded my spirit. In a secluded spot I sought my Heavenly Father.

“‘Lord,’ I prayed incessantly, ‘please send me a guru, one who can teach me to live by Thy light and not by food.’

“A divine ecstasy fell over me. Led by a beatific spell, I set out for the Nawabganj ghat on the Ganges. On the way I encountered the priest of my husband’s family.

“‘Venerable sir,’ I said trustingly, ‘kindly tell me how to live without eating.’

“He stared at me without reply. Finally he spoke in a consoling manner. ‘Child,’ he said, ‘come to the temple this evening; I will conduct a special Vedic ceremony for you.’

“This vague answer was not the one I was seeking; I continued toward the ghat. The morning sun pierced the waters; I purified myself in the Ganges, as though for a sacred initiation. As I left the river bank, my wet cloth around me, in the broad glare of day my master materialized himself before me!

“‘Dear little one,’ he said in a voice of loving compassion, ‘I am the guru sent here by God to fulfill your urgent prayer. He was deeply touched by its very unusual nature! From today you shall live by the astral light, your bodily atoms fed from the infinite current.’”

Giri Bala fell into silence. I took Mr. Wright’s pencil and pad and translated into English a few items for his information.

The saint resumed the tale, her gentle voice barely audible. “The ghat was deserted, but my guru cast round us an aura of guarding light, that no stray bathers later disturb us. He initiated me into a kria technique which frees the body from dependence on the gross food of mortals. The technique includes the use of a certain mantra 8 and a breathing exercise more difficult than the average person could perform. No medicine or magic is involved; nothing beyond the kria.”

In the manner of the American newspaper reporter, who had unknowingly taught me his procedure, I questioned Giri Bala on many matters which I thought would be of interest to the world. She gave me, bit by bit, the following information:

“I have never had any children; many years ago I became a widow. I sleep very little, as sleep and waking are the same to me. I meditate at night, attending to my domestic duties in the daytime. I slightly feel the change in climate from season to season. I have never been sick or experienced any disease. I feel only slight pain when accidentally injured. I have no bodily excretions. I can control my heart and breathing. I often see my guru as well as other great souls, in vision.”

“Mother,” I asked, “why don’t you teach others the method of living without food?”

My ambitious hopes for the world’s starving millions were nipped in the bud.

“No.” She shook her head. “I was strictly commanded by my guru not to divulge the secret. It is not his wish to tamper with God’s drama of creation. The farmers would not thank me if I taught many people to live without eating! The luscious fruits would lie uselessly on the ground. It appears that misery, starvation, and disease are whips of our karma which ultimately drive us to seek the true meaning of life.”

“Mother,” I said slowly, “what is the use of your having been singled out to live without eating?”

“To prove that man is Spirit.” Her face lit with wisdom. “To demonstrate that by divine advancement he can gradually learn to live by the Eternal Light and not by food.”

The saint sank into a deep meditative state. Her gaze was directed inward; the gentle depths of her eyes became expressionless. She gave a certain sigh, the prelude to the ecstatic breathless trance. For a time she had fled to the questionless realm, the heaven of inner joy.

The tropical darkness had fallen. The light of a small kerosene lamp flickered fitfully over the faces of a score of villagers squatting silently in the shadows. The darting glowworms and distant oil lanterns of the huts wove bright eerie patterns into the velvet night. It was the painful hour of parting; a slow, tedious journey lay before our little party.

“Giri Bala,” I said as the saint opened her eyes, “please give me a keepsake—a strip of one of your saris.”

She soon returned with a piece of Benares silk, extending it in her hand as she suddenly prostrated herself on the ground.

“Mother,” I said reverently, “rather let me touch your own blessed feet!”

-

In northern Bengal.▲

-

H. H. Sir Bijay Chand Mahtab, now dead. His family doubtless

possesses some record of the Maharaja’s three investigations of Giri

Bala.▲

-

Woman yogi.▲

-

“Remover of Obstacles,” the god of good fortune.▲

-

Sri Yukteswar used to say: “The Lord has given us the fruits

of the good earth. We like to see our food, to smell it, to taste it—the

Hindu likes also to touch it!” One does not mind hearing it, either, if no one else is present at the meal!▲

-

Mr. Wright also took moving pictures of Sri Yukteswar during his last Winter Solstice Festival in Serampore.▲

-

“What we eat is radiation; our food is so much quanta of

energy,” Dr. George W. Crile of Cleveland told a gathering of medical

men on May 17, 1933 in Memphis. “This all-important radiation, which

releases electrical currents for the body’s electrical circuit, the

nervous system, is given to food by the sun’s rays. Atoms, Dr. Crile

says, are solar systems. Atoms are the vehicles that are filled with

solar radiance as so many coiled springs. These countless atomfuls of

energy are taken in as food. Once in the human body, these tense

vehicles, the atoms, are discharged in the body’s protoplasm, the

radiance furnishing new chemical energy, new electrical currents. ‘Your

body is made up of such atoms,’ Dr. Crile said. ‘They are your muscles,

brains, and sensory organs, such as the eyes and ears.’”

Someday scientists will discover how man can live directly on solar energy. “Chlorophyll is the only substance known in nature that somehow possesses the power to act as a ‘sunlight trap,’” William L. Laurence writes in the New York Times. “It ‘catches’ the energy of sunlight and stores it in the plant. Without this no life could exist. We obtain the energy we need for living from the solar energy stored in the plant-food we eat or in the flesh of the animals that eat the plants. The energy we obtain from coal or oil is solar energy trapped by the chlorophyll in plant life millions of years ago. We live by the sun through the agency of chlorophyll.”▲

-

Potent vibratory chant. The literal translation of Sanskrit mantra

is “instrument of thought,” signifying the ideal, inaudible sounds

which represent one aspect of creation; when vocalized as syllables, a mantra

constitutes a universal terminology. The infinite powers of sound

derive from AUM, the “Word” or creative hum of the Cosmic Motor.▲

Chapter: 47

I Return to the West

“I have given many yoga lessons in India and America; but I must confess that, as a Hindu, I am unusually happy to be conducting a class for English students.”My London class members laughed appreciatively; no political turmoils ever disturbed our yoga peace.

India was now a hallowed memory. It is September, 1936; I am in England to fulfill a promise, given sixteen months earlier, to lecture again in London.

England, too, is receptive to the timeless yoga message. Reporters and newsreel cameramen swarmed over my quarters at Grosvenor House. The British National Council of the World Fellowship of Faiths organized a meeting on September 29th at Whitefield’s Congregational Church where I addressed the audience on the weighty subject of “How Faith in Fellowship may Save Civilization.” The eight o’clock lectures at Caxton Hall attracted such crowds that on two nights the overflow waited in Windsor House auditorium for my second talk at nine-thirty. Yoga classes during the following weeks grew so large that Mr. Wright was obliged to arrange a transfer to another hall.

The English tenacity has admirable expression in a spiritual relationship. The London yoga students loyally organized themselves, after my departure, into a Self-Realization Fellowship center, holding their meditation meetings weekly throughout the bitter war years.

Unforgettable weeks in England; days of sight-seeing in London, then over the beautiful countryside. Mr. Wright and I summoned the trusty Ford to visit the birthplaces and tombs of the great poets and heroes of British history.

Our little party sailed from Southampton for America in late October on the Bremen. The majestic Statue of Liberty in New York harbor brought a joyous emotional gulp not only to the throats of Miss Bletch and Mr. Wright, but to my own.

The Ford, a bit battered from struggles with ancient soils, was still puissant; it now took in its stride the transcontinental trip to California. In late 1936, lo! Mount Washington.

The year-end holidays are celebrated annually at the Los Angeles center with an eight-hour group meditation on December 24th (Spiritual Christmas), followed the next day by a banquet (Social Christmas). The festivities this year were augmented by the presence of dear friends and students from distant cities who had arrived to welcome home the three world travelers.

The Christmas Day feast included delicacies brought fifteen thousand miles for this glad occasion: gucchi mushrooms from Kashmir, canned rasagulla and mango pulp, papar biscuits, and an oil of the Indian keora flower which flavored our ice cream. The evening found us grouped around a huge sparkling Christmas tree, the near-by fireplace crackling with logs of aromatic cypress.

Gift-time! Presents from the earth’s far corners—Palestine, Egypt, India, England, France, Italy. How laboriously had Mr. Wright counted the trunks at each foreign junction, that no pilfering hand receive the treasures intended for loved ones in America! Plaques of the sacred olive tree from the Holy Land, delicate laces and embroideries from Belgium and Holland, Persian carpets, finely woven Kashmiri shawls, everlastingly fragrant sandalwood trays from Mysore, Shiva “bull’s eye” stones from Central Provinces, old Indian coins of dynasties long fled, bejeweled vases and cups, miniatures, tapestries, temple incense and perfumes, swadeshi cotton prints, lacquer work, Mysore ivory carvings, Persian slippers with their inquisitive long toe, quaint old illuminated manuscripts, velvets, brocades, Gandhi caps, potteries, tiles, brasswork, prayer rugs—booty of three continents!

One by one I distributed the gaily wrapped packages from the immense pile under the tree.

“Sister Gyanamata!” I handed a long box to the saintly American lady of sweet visage and deep realization who, during my absence, had been in charge at Mt. Washington. From the paper tissues she lifted a sari of golden Benares silk.

“Thank you, sir; it brings the pageant of India before my eyes.”

“Mr. Dickinson!” The next parcel contained a gift which I had bought in a Calcutta bazaar. “Mr. Dickinson will like this,” I had thought at the time. A dearly beloved disciple, Mr. Dickinson had been present at every Christmas festivity since the 1925 founding of Mt. Washington. At this eleventh annual celebration, he was standing before me, untying the ribbons of his square little package.

Mr. E. E. Dickinson of Los Angeles; he sought a silver cup.

Sri Yukteswar and myself in Calcutta, 1935. He is carrying the gift umbrella-cane.

A group of Ranchi

students and teachers pose with the venerable Maharaja of Kasimbazar (at

center, in white). In 1918 he gave his Kasimbazar Palace and

twenty-five acres in Ranchi as a permanent site for my yoga school for

boys.

The ejaculatory evening closed with a prayer to the Giver of all gifts; then a group singing of Christmas carols.

Mr. Dickinson and I were chatting together sometime later.

“Sir,” he said, “please let me thank you now for the silver cup. I could not find any words on Christmas night.”

“I brought the gift especially for you.”

“For forty-three years I have been waiting for that silver cup! It is a long story, one I have kept hidden within me.” Mr. Dickinson looked at me shyly. “The beginning was dramatic: I was drowning. My older brother had playfully pushed me into a fifteen-foot pool in a small town in Nebraska. I was only five years old then. As I was about to sink for the second time under the water, a dazzling multicolored light appeared, filling all space. In the midst was the figure of a man with tranquil eyes and a reassuring smile. My body was sinking for the third time when one of my brother’s companions bent a tall slender willow tree in such a low dip that I could grasp it with my desperate fingers. The boys lifted me to the bank and successfully gave me first-aid treatment.