The great guru encouraged his

various students to adhere to the good traditional discipline of their

own faith. Stressing the all-inclusive nature of Kriya as a

practical technique of liberation, Lahiri Mahasaya then gave his chelas

liberty to express their lives in conformance with environment and up

bringing.

“A Moslem should perform his namaj 13 worship four times daily,” the master pointed out. “Four times daily a Hindu should sit in meditation. A Christian should go down on his knees four times daily, praying to God and then reading the Bible.”

With wise discernment the guru guided his followers into the paths of Bhakti (devotion), Karma (action), Jnana (wisdom), or Raja (royal or complete) Yogas, according to each man’s natural tendencies. The master, who was slow to give his permission to devotees wishing to enter the formal path of monkhood, always cautioned them to first reflect well on the austerities of the monastic life.

The great guru taught his disciples to avoid theoretical discussion of the scriptures. “He only is wise who devotes himself to realizing, not reading only, the ancient revelations,” he said. “Solve all your problems through meditation.14 Exchange unprofitable religious speculations for actual God-contact. Clear your mind of dogmatic theological debris; let in the fresh, healing waters of direct perception. Attune yourself to the active inner Guidance; the Divine Voice has the answer to every dilemma of life. Though man’s ingenuity for getting himself into trouble appears to be endless, the Infinite Succor is no less resourceful.”

The master’s omnipresence was demonstrated one day before a group of disciples who were listening to his exposition of the Bhagavad Gita. As he was explaining the meaning of Kutastha Chaitanya or the Christ Consciousness in all vibratory creation, Lahiri Mahasaya suddenly gasped and cried out:

“I am drowning in the bodies of many souls off the coast of Japan!”

The next morning the chelas read a newspaper account of the death of many people whose ship had foundered the preceding day near Japan.

The distant disciples of Lahiri Mahasaya were often made aware of his enfolding presence. “I am ever with those who practice Kriya,” he said consolingly to chelas who could not remain near him. “I will guide you to the Cosmic Home through your enlarging perceptions.”

Swami Satyananda was told by a devotee that, unable to go to Benares, the man had nevertheless received precise Kriya initiation in a dream. Lahiri Mahasaya had appeared to instruct the chela in answer to his prayers.

If a disciple neglected any of his worldly obligations, the master would gently correct and discipline him.

“Lahiri Mahasaya’s words were mild and healing, even when he was forced to speak openly of a chela’s faults,” Sri Yukteswar once told me. He added ruefully, “No disciple ever fled from our master’s barbs.” I could not help laughing, but I truthfully assured Sri Yukteswar that, sharp or not, his every word was music to my ears.

Lahiri Mahasaya carefully graded Kriya into four progressive initiations.15 He bestowed the three higher techniques only after the devotee had manifested definite spiritual progress. One day a certain chela, convinced that his worth was not being duly evaluated, gave voice to his discontent.

“Master,” he said, “surely I am ready now for the second initiation.”

At this moment the door opened to admit a humble disciple, Brinda Bhagat. He was a Benares postman.

“Brinda, sit by me here.” The great guru smiled at him affectionately. “Tell me, are you ready for the second technique of Kriya?”

The little postman folded his hands in supplication. “Gurudeva,” he said in alarm, “no more initiations, please! How can I assimilate any higher teachings? I have come today to ask your blessings, because the first divine Kriya has filled me with such intoxication that I cannot deliver my letters!”

“Already Brinda swims in the sea of Spirit.” At these words from Lahiri Mahasaya, his other disciple hung his head.

“Master,” he said, “I see I have been a poor workman, finding fault with my tools.”

The postman, who was an uneducated man, later developed his insight through Kriya to such an extent that scholars occasionally sought his interpretation on involved scriptural points. Innocent alike of sin and syntax, little Brinda won renown in the domain of learned pundits.

Besides the numerous Benares disciples of Lahiri Mahasaya, hundreds came to him from distant parts of India. He himself traveled to Bengal on several occasions, visiting at the homes of the fathers-in-law of his two sons. Thus blessed by his presence, Bengal became honeycombed with small Kriya groups. Particularly in the districts of Krishnagar and Bishnupur, many silent devotees to this day have kept the invisible current of spiritual meditation flowing.

Among many saints who received Kriya from Lahiri Mahasaya may be mentioned the illustrious Swami Vhaskarananda Saraswati of Benares, and the Deogarh ascetic of high stature, Balananda Brahmachari. For a time Lahiri Mahasaya served as private tutor to the son of Maharaja Iswari Narayan Sinha Bahadur of Benares. Recognizing the master’s spiritual attainment, the maharaja, as well as his son, sought Kriya initiation, as did the Maharaja Jotindra Mohan Thakur.

A number of Lahiri Mahasaya’s disciples with influential worldly position were desirous of expanding the Kriya circle by publicity. The guru refused his permission. One chela, the royal physician to the Lord of Benares, started an organized effort to spread the master’s name as “Kashi Baba” (Exalted One of Benares).16 Again the guru forbade it.

“Let the fragrance of the Kriya flower be wafted naturally, without any display,” he said. “Its seeds will take root in the soil of spiritually fertile hearts.”

Although the great master did not adopt the system of preaching through the modern medium of an organization, or through the printing press, he knew that the power of his message would rise like a resistless flood, inundating by its own force the banks of human minds. The changed and purified lives of devotees were the simple guarantees of the deathless vitality of Kriya.

In 1886, twenty-five years after his Ranikhet initiation, Lahiri Mahasaya was retired on a pension.17 With his availability in the daytime, disciples sought him out in ever-increasing numbers. The great guru now sat in silence most of the time, locked in the tranquil lotus posture. He seldom left his little parlor, even for a walk or to visit other parts of the house. A quiet stream of chelas arrived, almost ceaselessly, for a darshan (holy sight) of the guru.

To the awe of all beholders, Lahiri Mahasaya’s habitual physiological state exhibited the superhuman features of breathlessness, sleeplessness, cessation of pulse and heartbeat, calm eyes unblinking for hours, and a profound aura of peace. No visitors departed without upliftment of spirit; all knew they had received the silent blessing of a true man of God.

The master now permitted his disciple, Panchanon Bhattacharya, to open an “Arya Mission Institution” in Calcutta. Here the saintly disciple spread the message of Kriya Yoga, and prepared for public benefit certain yogic herbal 18 medicines.

In accordance with ancient custom, the master gave to people in general a neem 19 oil for the cure of various diseases. When the guru requested a disciple to distil the oil, he could easily accomplish the task. If anyone else tried, he would encounter strange difficulties, finding that the medicinal oil had almost evaporated after going through the required distilling processes. Evidently the master’s blessing was a necessary ingredient.

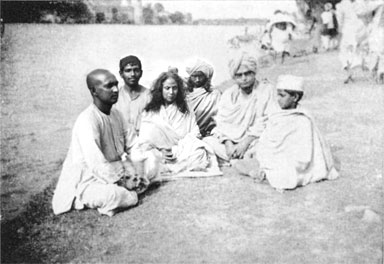

Lahiri Mahasaya’s handwriting and signature, in Bengali script, are shown above. The lines occur in a letter to a chela; the great master interprets a Sanskrit verse as follows: “He who has attained a state of calmness wherein his eyelids do not blink, has achieved Sambhabi Mudra.”

(signed) “Sri Shyama Charan Deva Sharman”

The Arya Mission Institution undertook the publication of many of the guru’s scriptural commentaries. Like Jesus and other great prophets, Lahiri Mahasaya himself wrote no books, but his penetrating interpretations were recorded and arranged by various disciples. Some of these voluntary amanuenses were more discerning than others in correctly conveying the profound insight of the guru; yet, on the whole, their efforts were successful. Through their zeal, the world possesses unparalleled commentaries by Lahiri Mahasaya on twenty-six ancient scriptures.

Sri Ananda Mohan Lahiri, a grandson of the master, has written an interesting booklet on Kriya. “The text of the Bhagavad Gita is a part of the great epic, the Mahabharata, which possesses several knot-points (vyas-kutas),” Sri Ananda wrote. “Keep those knot-points unquestioned, and we find nothing but mythical stories of a peculiar and easily-misunderstood type. Keep those knot-points unexplained, and we have lost a science which the East has preserved with superhuman patience after a quest of thousands of years of experiment.20 It was the commentaries of Lahiri Mahasaya which brought to light, clear of allegories, the very science of religion that had been so cleverly put out of sight in the riddle of scriptural letters and imagery. No longer a mere unintelligible jugglery of words, the otherwise unmeaning formulas of Vedic worship have been proved by the master to be full of scientific significance. . . .

“We know that man is usually helpless against the insurgent sway of evil passions, but these are rendered powerless and man finds no motive in their indulgence when there dawns on him a consciousness of superior and lasting bliss through Kriya. Here the give-up, the negation of the lower passions, synchronizes with a take-up, the assertion of a beatitude. Without such a course, hundreds of moral maxims which run in mere negatives are useless to us.

“Our eagerness for worldly activity kills in us the sense of spiritual awe. We cannot comprehend the Great Life behind all names and forms, just because science brings home to us how we can use the powers of nature; this familiarity has bred a contempt for her ultimate secrets. Our relation with nature is one of practical business. We tease her, so to speak, to know how she can be used to serve our purposes; we make use of her energies, whose Source yet remains unknown. In science our relation with nature is one that exists between a man and his servant, or in a philosophical sense she is like a captive in the witness box. We cross-examine her, challenge her, and minutely weigh her evidence in human scales which cannot measure her hidden values. On the other hand, when the self is in communion with a higher power, nature automatically obeys, without stress or strain, the will of man. This effortless command over nature is called ‘miraculous’ by the uncomprehending materialist.

“The life of Lahiri Mahasaya set an example which changed the erroneous notion that yoga is a mysterious practice. Every man may find a way through Kriya to understand his proper relation with nature, and to feel spiritual reverence for all phenomena, whether mystical or of everyday occurrence, in spite of the matter-of-factness of physical science.21 We must bear in mind that what was mystical a thousand years ago is no longer so, and what is mysterious now may become lawfully intelligible a hundred years hence. It is the Infinite, the Ocean of Power, that is at the back of all manifestations.

“The law of Kriya Yoga is eternal. It is true like mathematics; like the simple rules of addition and subtraction, the law of Kriya can never be destroyed. Burn to ashes all the books on mathematics, the logically-minded will always rediscover such truths; destroy all the sacred books on yoga, its fundamental laws will come out whenever there appears a true yogi who comprises within himself pure devotion and consequently pure knowledge.”

Just as Babaji is among the greatest of avatars, a Mahavatar, and Sri Yukteswar a Jnanavatar or Incarnation of Wisdom, so Lahiri Mahasaya may justly be called Yogavatar, or Incarnation of Yoga. By the standards of both qualitative and quantitative good, he elevated the spiritual level of society. In his power to raise his close disciples to Christlike stature and in his wide dissemination of truth among the masses, Lahiri Mahasaya ranks among the saviors of mankind.

His uniqueness as a prophet lies in his practical stress on a definite method, Kriya, opening for the first time the doors of yoga freedom to all men. Apart from the miracles of his own life, surely the Yogavatar reached the zenith of all wonders in reducing the ancient complexities of yoga to an effective simplicity not beyond the ordinary grasp.

In reference to miracles, Lahiri Mahasaya often said, “The operation of subtle laws which are unknown to people in general should not be publicly discussed or published without due discrimination.” If in these pages I have appeared to flout his cautionary words, it is because he has given me an inward reassurance. Also, in recording the lives of Babaji, Lahiri Mahasaya, and Sri Yukteswar, I have thought it advisable to omit many true miraculous stories, which could hardly have been included without writing, also, an explanatory volume of abstruse philosophy.

New hope for new men! “Divine union,” the Yogavatar proclaimed, “is possible through self-effort, and is not dependent on theological beliefs or on the arbitrary will of a Cosmic Dictator.”

Through use of the Kriya key, persons who cannot bring themselves to believe in the divinity of any man will behold at last the full divinity of their own selves.

The religious fairs held in India since time immemorial are known as Kumbha Melas; they have kept spiritual goals in constant sight of the multitude. Devout Hindus gather by the millions every six years to meet thousands of sadhus, yogis, swamis, and ascetics of all kinds. Many are hermits who never leave their secluded haunts except to attend the melas and bestow their blessings on worldly men and women.

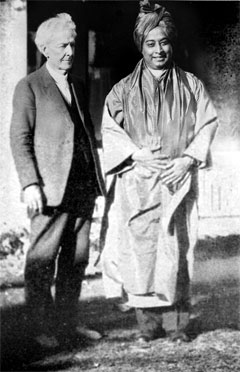

“I was not a swami at the time I met Babaji,” Sri Yukteswar went on. “But I had already received Kriya initiation from Lahiri Mahasaya. He encouraged me to attend the mela which was convening in January, 1894 at Allahabad. It was my first experience of a kumbha; I felt slightly dazed by the clamor and surge of the crowd. In my searching gazes around I saw no illumined face of a master. Passing a bridge on the bank of the Ganges, I noticed an acquaintance standing near-by, his begging bowl extended.

“‘Oh, this fair is nothing but a chaos of noise and beggars,’ I thought in disillusionment. ‘I wonder if Western scientists, patiently enlarging the realms of knowledge for the practical good of mankind, are not more pleasing to God than these idlers who profess religion but concentrate on alms.’

“My smouldering reflections on social reform were interrupted by the voice of a tall sannyasi who halted before me.

“‘Sir,’ he said, ‘a saint is calling you.’

“‘Who is he?’

“‘Come and see for yourself.’

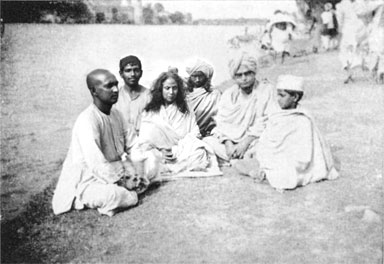

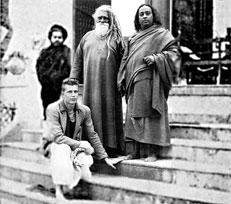

“Hesitantly following this laconic advice, I soon found myself near a tree whose branches were sheltering a guru with an attractive group of disciples. The master, a bright unusual figure, with sparkling dark eyes, rose at my approach and embraced me.

“‘Welcome, Swamiji,’ he said affectionately.

“‘Sir,’ I replied emphatically, ‘I am not a swami.’

“‘Those on whom I am divinely directed to bestow the title of “swami” never cast it off.’ The saint addressed me simply, but deep conviction of truth rang in his words; I was engulfed in an instant wave of spiritual blessing. Smiling at my sudden elevation into the ancient monastic order,1 I bowed at the feet of the obviously great and angelic being in human form who had thus honored me.

“Babaji—for it was indeed he—motioned me to a seat near him under the tree. He was strong and young, and looked like Lahiri Mahasaya; yet the resemblance did not strike me, even though I had often heard of the extraordinary similarities in the appearance of the two masters. Babaji possesses a power by which he can prevent any specific thought from arising in a person’s mind. Evidently the great guru wished me to be perfectly natural in his presence, not overawed by knowledge of his identity.

“‘What do you think of the Kumbha Mela?’

“‘I was greatly disappointed, sir.’ I added hastily, ‘Up until the time I met you. Somehow saints and this commotion don’t seem to belong together.’

“‘Child,’ the master said, though apparently I was nearly twice his own age, ‘for the faults of the many, judge not the whole. Everything on earth is of mixed character, like a mingling of sand and sugar. Be like the wise ant which seizes only the sugar, and leaves the sand untouched. Though many sadhus here still wander in delusion, yet the mela is blessed by a few men of God-realization.’

“In view of my own meeting with this exalted master, I quickly agreed with his observation.

“‘Sir,’ I commented, ‘I have been thinking of the scientific men of the West, greater by far in intelligence than most people congregated here, living in distant Europe and America, professing different creeds, and ignorant of the real values of such melas as the present one. They are the men who could benefit greatly by meetings with India’s masters. But, although high in intellectual attainments, many Westerners are wedded to rank materialism. Others, famous in science and philosophy, do not recognize the essential unity in religion. Their creeds serve as insurmountable barriers that threaten to separate them from us forever.’

“‘I saw that you are interested in the West, as well as the East.’ Babaji’s face beamed with approval. ‘I felt the pangs of your heart, broad enough for all men, whether Oriental or Occidental. That is why I summoned you here.

“‘East and West must establish a golden middle path of activity and spirituality combined,’ he continued. ‘India has much to learn from the West in material development; in return, India can teach the universal methods by which the West will be able to base its religious beliefs on the unshakable foundations of yogic science.

“‘You, Swamiji, have a part to play in the coming harmonious exchange between Orient and Occident. Some years hence I shall send you a disciple whom you can train for yoga dissemination in the West. The vibrations there of many spiritually seeking souls come floodlike to me. I perceive potential saints in America and Europe, waiting to be awakened.’”

At this point in his story, Sri Yukteswar turned his gaze fully on mine.

“My son,” he said, smiling in the moonlight, “you are the disciple that, years ago, Babaji promised to send me.”

I was happy to learn that Babaji had directed my steps to Sri Yukteswar, yet it was hard for me to visualize myself in the remote West, away from my beloved guru and the simple hermitage peace.

“Babaji then spoke of the Bhagavad Gita,” Sri Yukteswar went on. “To my astonishment, he indicated by a few words of praise that he was aware of the fact that I had written interpretations on various Gita chapters.

“‘At my request, Swamiji, please undertake another task,’ the great master said. ‘Will you not write a short book on the underlying basic unity between the Christian and Hindu scriptures? Show by parallel references that the inspired sons of God have spoken the same truths, now obscured by men’s sectarian differences.’

“‘Maharaj,’ 2 I answered diffidently, ‘what a command! Shall I be able to fulfill it?’

“Babaji laughed softly. ‘My son, why do you doubt?’ he said reassuringly. ‘Indeed, Whose work is all this, and Who is the Doer of all actions? Whatever the Lord has made me say is bound to materialize as truth.’

“I deemed myself empowered by the blessings of the saint, and agreed to write the book. Feeling reluctantly that the parting-hour had arrived, I rose from my leafy seat.

“‘Do you know Lahiri?’ 3 the master inquired. ‘He is a great soul, isn’t he? Tell him of our meeting.’ He then gave me a message for Lahiri Mahasaya.

“After I had bowed humbly in farewell, the saint smiled benignly. ‘When your book is finished, I shall pay you a visit,’ he promised. ‘Good-by for the present.’

“I left Allahabad the following day and entrained for Benares. Reaching my guru’s home, I poured out the story of the wonderful saint at the Kumbha Mela.

“‘Oh, didn’t you recognize him?’ Lahiri Mahasaya’s eyes were dancing with laughter. ‘I see you couldn’t, for he prevented you. He is my incomparable guru, the celestial Babaji!’

“‘Babaji!’ I repeated, awestruck. ‘The Yogi-Christ Babaji! The invisible-visible savior Babaji! Oh, if I could just recall the past and be once more in his presence, to show my devotion at his lotus feet!’

“‘Never mind,’ Lahiri Mahasaya said consolingly. ‘He has promised to see you again.’

“‘Gurudeva, the divine master asked me to give you a message. “Tell Lahiri,” he said, “that the stored-up power for this life now runs low; it is nearly finished.”’

“At my utterance of these enigmatic words, Lahiri Mahasaya’s figure trembled as though touched by a lightning current. In an instant everything about him fell silent; his smiling countenance turned incredibly stern. Like a wooden statue, somber and immovable in its seat, his body became colorless. I was alarmed and bewildered. Never in my life had I seen this joyous soul manifest such awful gravity. The other disciples present stared apprehensively.

“Three hours passed in utter silence. Then Lahiri Mahasaya resumed his natural, cheerful demeanor, and spoke affectionately to each of the chelas. Everyone sighed in relief.

“I realized by my master’s reaction that Babaji’s message had been an unmistakable signal by which Lahiri Mahasaya understood that his body would soon be untenanted. His awesome silence proved that my guru had instantly controlled his being, cut his last cord of attachment to the material world, and fled to his ever-living identity in Spirit. Babaji’s remark had been his way of saying: ‘I shall be ever with you.’

“Though Babaji and Lahiri Mahasaya were omniscient, and had no need of communicating with each other through me or any other intermediary, the great ones often condescend to play a part in the human drama. Occasionally they transmit their prophecies through messengers in an ordinary way, that the final fulfillment of their words may infuse greater divine faith in a wide circle of men who later learn the story.

“I soon left Benares, and set to work in Serampore on the scriptural writings requested by Babaji,” Sri Yukteswar continued. “No sooner had I begun my task than I was able to compose a poem dedicated to the deathless guru. The melodious lines flowed effortlessly from my pen, though never before had I attempted Sanskrit poetry.

“In the quiet of night I busied myself over a comparison of the Bible and the scriptures of Sanatan Dharma.4 Quoting the words of the blessed Lord Jesus, I showed that his teachings were in essence one with the revelations of the Vedas. To my relief, my book was finished in a short time; I realized that this speedy blessing was due to the grace of my Param-Guru-Maharaj.5 The chapters first appeared in the Sadhusambad journal; later they were privately printed as a book by one of my Kidderpore disciples.

“The morning after I had concluded my literary efforts,” Master continued, “I went to the Rai Ghat here to bathe in the Ganges. The ghat was deserted; I stood still for awhile, enjoying the sunny peace. After a dip in the sparkling waters, I started for home. The only sound in the silence was that of my Ganges-drenched cloth, swish-swashing with every step. As I passed beyond the site of the large banyan tree near the river bank, a strong impulse urged me to look back. There, under the shade of the banyan, and surrounded by a few disciples, sat the great Babaji!

“‘Greetings, Swamiji!’ The beautiful voice of the master rang out to assure me I was not dreaming. ‘I see you have successfully completed your book. As I promised, I am here to thank you.’

“With a fast-beating heart, I prostrated myself fully at his feet. ‘Param-guruji,’ I said imploringly, ‘will you and your chelas not honor my near-by home with your presence?’

“The supreme guru smilingly declined. ‘No, child,’ he said, ‘we are people who like the shelter of trees; this spot is quite comfortable.’

“‘Please tarry awhile, Master.’ I gazed entreatingly at him. ‘I shall be back at once with some special sweetmeats.’

“When I returned in a few minutes with a dish of delicacies, lo! the lordly banyan no longer sheltered the celestial troupe. I searched all around the ghat, but in my heart I knew the little band had already fled on etheric wings.

“I was deeply hurt. ‘Even if we meet again, I would not care to talk to him,’ I assured myself. ‘He was unkind to leave me so suddenly.’ This was a wrath of love, of course, and nothing more.

“A few months later I visited Lahiri Mahasaya in Benares. As I entered his little parlor, my guru smiled in greeting.

“‘Welcome, Yukteswar,’ he said. ‘Did you just meet Babaji at the threshold of my room?’

“‘Why, no,’ I answered in surprise.

“‘Come here.’ Lahiri Mahasaya touched me gently on the forehead; at once I beheld, near the door, the form of Babaji, blooming like a perfect lotus.

“I remembered my old hurt, and did not bow. Lahiri Mahasaya looked at me in astonishment.

“The divine guru gazed at me with fathomless eyes. ‘You are annoyed with me.’

“‘Sir, why shouldn’t I be?’ I answered. ‘Out of the air you came with your magic group, and into the thin air you vanished.’

“‘I told you I would see you, but didn’t say how long I would remain.’ Babaji laughed softly. ‘You were full of excitement. I assure you that I was fairly extinguished in the ether by the gust of your restlessness.’

“I was instantly satisfied by this unflattering explanation. I knelt at his feet; the supreme guru patted me kindly on the shoulder.

“‘Child, you must meditate more,’ he said. ‘Your gaze is not yet faultless—you could not see me hiding behind the sunlight.’ With these words in the voice of a celestial flute, Babaji disappeared into the hidden radiance.

“That was one of my last visits to Benares to see my guru,” Sri Yukteswar concluded. “Even as Babaji had foretold at the Kumbha Mela, the householder-incarnation of Lahiri Mahasaya was drawing to a close. During the summer of 1895 his stalwart body developed a small boil on the back. He protested against lancing; he was working out in his own flesh the evil karma of some of his disciples. Finally a few chelas became very insistent; the master replied cryptically:

“‘The body has to find a cause to go; I will be agreeable to whatever you want to do.’

“A short time later the incomparable guru gave up his body in Benares. No longer need I seek him out in his little parlor; I find every day of my life blessed by his omnipresent guidance.”

Years later, from the lips of Swami Keshabananda,6 an advanced disciple, I heard many wonderful details about the passing of Lahiri Mahasaya.

“A few days before my guru relinquished his body,” Keshabananda told me, “he materialized himself before me as I sat in my hermitage at Hardwar.

“‘Come at once to Benares.’ With these words Lahiri Mahasaya vanished.

“I entrained immediately for Benares. At my guru’s home I found many disciples assembled. For hours that day 7 the master expounded the Gita; then he addressed us simply.

“‘I am going home.’

“Sobs of anguish broke out like an irresistible torrent.

“‘Be comforted; I shall rise again.’ After this utterance Lahiri Mahasaya thrice turned his body around in a circle, faced the north in his lotus posture, and gloriously entered the final maha-samadhi.8

“Lahiri Mahasaya’s beautiful body, so dear to the devotees, was cremated with solemn householder rites at Manikarnika Ghat by the holy Ganges,” Keshabananda continued. “The following day, at ten o’clock in the morning, while I was still in Benares, my room was suffused with a great light. Lo! before me stood the flesh and blood form of Lahiri Mahasaya! It looked exactly like his old body, except that it appeared younger and more radiant. My divine guru spoke to me.

“‘Keshabananda,’ he said, ‘it is I. From the disintegrated atoms of my cremated body, I have resurrected a remodeled form. My householder work in the world is done; but I do not leave the earth entirely. Henceforth I shall spend some time with Babaji in the Himalayas, and with Babaji in the cosmos.’

“With a few words of blessing to me, the transcendent master vanished. Wondrous inspiration filled my heart; I was uplifted in Spirit even as were the disciples of Christ and Kabir 9 when they had gazed on their living gurus after physical death.

“When I returned to my isolated Hardwar hermitage,” Keshabananda went on, “I carried with me the sacred ashes of my guru. I know he has escaped the spatio-temporal cage; the bird of omnipresence is freed. Yet it comforted my heart to enshrine his sacred remains.”

Another disciple who was blessed by the sight of his resurrected guru was the saintly Panchanon Bhattacharya, founder of the Calcutta Arya Mission Institution.10

I visited Panchanon at his Calcutta home, and listened with delight to the story of his many years with the master. In conclusion, he told me of the most marvelous event in his life.

“Here in Calcutta,” Panchanon said, “at ten o’clock of the morning which followed his cremation, Lahiri Mahasaya appeared before me in living glory.”

Swami Pranabananda, the “saint with two bodies,” also confided to me the details of his own supernal experience.

“A few days before Lahiri Mahasaya left his body,” Pranabananda told me at the time he visited my Ranchi school, “I received a letter from him, requesting me to come at once to Benares. I was delayed, however, and could not leave immediately. As I was in the midst of my travel preparations, about ten o’clock in the morning, I was suddenly overwhelmed with joy to see the shining figure of my guru.

“‘Why hurry to Benares?’ Lahiri Mahasaya said, smiling. ‘You shall find me there no longer.’

“As the import of his words dawned on me, I sobbed broken-heartedly, believing that I was seeing him only in a vision.

“The master approached me comfortingly. ‘Here, touch my flesh,’ he said. ‘I am living, as always. Do not lament; am I not with you forever?’”

From the lips of these three great disciples, a story of wondrous truth has emerged: At the morning hour of ten, on the day after the body of Lahiri Mahasaya had been consigned to the flames, the resurrected master, in a real but transfigured body, appeared before three disciples, each one in a different city.

“So when this corruptible shall have put on incorruption, and this mortal shall have put on immortality, then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written, Death is swallowed up in victory. O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?” 11

Immersed in meditation, I was sitting behind some dusty boxes in the storeroom of the Ranchi school. A private spot was difficult to find during those busy years with the youngsters!

The vision continued; a vast multitude,1 gazing at me intently, swept actorlike across the stage of consciousness.

The storeroom door opened; as usual, one of the young lads had discovered my hiding place.

“Come here, Bimal,” I cried gaily. “I have news for you: the Lord is calling me to America!”

“To America?” The boy echoed my words in a tone that implied I had said “to the moon.”

“Yes! I am going forth to discover America, like Columbus. He thought he had found India; surely there is a karmic link between those two lands!”

Bimal scampered away; soon the whole school was informed by the two-legged newspaper.2 I summoned the bewildered faculty and gave the school into its charge.

“I know you will keep Lahiri Mahasaya’s yoga ideals of education ever to the fore,” I said. “I shall write you frequently; God willing, someday I shall be back.”

Tears stood in my eyes as I cast a last look at the little boys and the sunny acres of Ranchi. A definite epoch in my life had now closed, I knew; henceforth I would dwell in far lands. I entrained for Calcutta a few hours after my vision. The following day I received an invitation to serve as the delegate from India to an International Congress of Religious Liberals in America. It was to convene that year in Boston, under the auspices of the American Unitarian Association.

My head in a whirl, I sought out Sri Yukteswar in Serampore.

“Guruji, I have just been invited to address a religious congress in America. Shall I go?”

“All doors are open for you,” Master replied simply. “It is now or never.”

“But, sir,” I said in dismay, “what do I know about public speaking? Seldom have I given a lecture, and never in English.”

“English or no English, your words on yoga shall be heard in the West.”

I laughed. “Well, dear guruji, I hardly think the Americans will learn Bengali! Please bless me with a push over the hurdles of the English language.” 3

When I broke the news of my plans to Father, he was utterly taken aback. To him America seemed incredibly remote; he feared he might never see me again.

“How can you go?” he asked sternly. “Who will finance you?” As he had affectionately borne the expenses of my education and whole life, he doubtless hoped that his question would bring my project to an embarrassing halt.

“The Lord will surely finance me.” As I made this reply, I thought of the similar one I had given long ago to my brother Ananta in Agra. Without very much guile, I added, “Father, perhaps God will put it into your mind to help me.”

“No, never!” He glanced at me piteously.

I was astounded, therefore, when Father handed me, the following day, a check made out for a large amount.

“I give you this money,” he said, “not in my capacity as a father, but as a faithful disciple of Lahiri Mahasaya. Go then to that far Western land; spread there the creedless teachings of Kriya Yoga.”

I was immensely touched at the selfless spirit in which Father had been able to quickly put aside his personal desires. The just realization had come to him during the preceding night that no ordinary desire for foreign travel was motivating my voyage.

“Perhaps we shall not meet again in this life.” Father, who was sixty-seven at this time, spoke sadly.

An intuitive conviction prompted me to reply, “Surely the Lord will bring us together once more.”

As I went about my preparations to leave Master and my native land for the unknown shores of America, I experienced not a little trepidation. I had heard many stories about the materialistic Western atmosphere, one very different from the spiritual background of India, pervaded with the centuried aura of saints. “An Oriental teacher who will dare the Western airs,” I thought, “must be hardy beyond the trials of any Himalayan cold!”

One early morning I began to pray, with an adamant determination to continue, to even die praying, until I heard the voice of God. I wanted His blessing and assurance that I would not lose myself in the fogs of modern utilitarianism. My heart was set to go to America, but even more strongly was it resolved to hear the solace of divine permission.

I prayed and prayed, muffling my sobs. No answer came. My silent petition increased in excruciating crescendo until, at noon, I had reached a zenith; my brain could no longer withstand the pressure of my agonies. If I cried once more with an increased depth of my inner passion, I felt as though my brain would split. At that moment there came a knock outside the vestibule adjoining the Gurpar Road room in which I was sitting. Opening the door, I saw a young man in the scanty garb of a renunciate. He came in, closed the door behind him and, refusing my request to sit down, indicated with a gesture that he wished to talk to me while standing.

“He must be Babaji!” I thought, dazed, because the man before me had the features of a younger Lahiri Mahasaya.

He answered my thought. “Yes, I am Babaji.” He spoke melodiously in Hindi. “Our Heavenly Father has heard your prayer. He commands me to tell you: Follow the behests of your guru and go to America. Fear not; you will be protected.”

After a vibrant pause, Babaji addressed me again. “You are the one I have chosen to spread the message of Kriya Yoga in the West. Long ago I met your guru Yukteswar at a Kumbha Mela; I told him then I would send you to him for training.”

I was speechless, choked with devotional awe at his presence, and deeply touched to hear from his own lips that he had guided me to Sri Yukteswar. I lay prostrate before the deathless guru. He graciously lifted me from the floor. Telling me many things about my life, he then gave me some personal instruction, and uttered a few secret prophecies.

“Kriya Yoga, the scientific technique of God-realization,” he finally said with solemnity, “will ultimately spread in all lands, and aid in harmonizing the nations through man’s personal, transcendental perception of the Infinite Father.”

With a gaze of majestic power, the master electrified me by a glimpse of his cosmic consciousness. In a short while he started toward the door.

“Do not try to follow me,” he said. “You will not be able to do so.”

“Please, Babaji, don’t go away!” I cried repeatedly. “Take me with you!”

Looking back, he replied, “Not now. Some other time.”

Overcome by emotion, I disregarded his warning. As I tried to pursue him, I discovered that my feet were firmly rooted to the floor. From the door, Babaji gave me a last affectionate glance. He raised his hand by way of benediction and walked away, my eyes fixed on him longingly.

After a few minutes my feet were free. I sat down and went into a deep meditation, unceasingly thanking God not only for answering my prayer but for blessing me by a meeting with Babaji. My whole body seemed sanctified through the touch of the ancient, ever-youthful master. Long had it been my burning desire to behold him.

Until now, I have never recounted to anyone this story of my meeting with Babaji. Holding it as the most sacred of my human experiences, I have hidden it in my heart. But the thought occurred to me that readers of this autobiography may be more inclined to believe in the reality of the secluded Babaji and his world interests if I relate that I saw him with my own eyes. I have helped an artist to draw a true picture of the great Yogi-Christ of modern India; it appears in this book.

The eve of my departure for the United States found me in Sri Yukteswar’s holy presence.

“Forget you were born a Hindu, and don’t be an American. Take the best of them both,” Master said in his calm way of wisdom. “Be your true self, a child of God. Seek and incorporate into your being the best qualities of all your brothers, scattered over the earth in various races.”

Then he blessed me: “All those who come to you with faith,

seeking God, will be helped. As you look at them, the spiritual current

emanating from your eyes will enter into their brains and change their

material habits, making them more God-conscious.”

He went on, “Your lot to attract sincere souls is very good. Everywhere you go, even in a wilderness, you will find friends.”

Both of his blessings have been amply demonstrated. I came alone to America, into a wilderness without a single friend, but there I found thousands ready to receive the time-tested soul-teachings.

I left India in August, 1920, on The City of Sparta, the first passenger boat sailing for America after the close of World War I. I had been able to book passage only after the removal, in ways fairly miraculous, of many “red-tape” difficulties concerned with the granting of my passport.

During the two-months’ voyage a fellow passenger found out that I was the Indian delegate to the Boston congress.

“Swami Yogananda,” he said, with the first of many quaint pronunciations by which I was later to hear my name spoken by the Americans, “please favor the passengers with a lecture next Thursday night. I think we would all benefit by a talk on ‘The Battle of Life and How to Fight It.’”

Alas! I had to fight the battle of my own life, I discovered on Wednesday. Desperately trying to organize my ideas into a lecture in English, I finally abandoned all preparations; my thoughts, like a wild colt eyeing a saddle, refused any cooperation with the laws of English grammar. Fully trusting in Master’s past assurances, however, I appeared before my Thursday audience in the saloon of the steamer. No eloquence rose to my lips; speechlessly I stood before the assemblage. After an endurance contest lasting ten minutes, the audience realized my predicament and began to laugh.

The situation was not funny to me at the moment; indignantly I sent a silent prayer to Master.

“You can! Speak!” His voice sounded instantly within my consciousness.

My thoughts fell at once into a friendly relation with the English language. Forty-five minutes later the audience was still attentive. The talk won me a number of invitations to lecture later before various groups in America.

I never could remember, afterward, a word that I had spoken. By discreet inquiry I learned from a number of passengers: “You gave an inspiring lecture in stirring and correct English.” At this delightful news I humbly thanked my guru for his timely help, realizing anew that he was ever with me, setting at naught all barriers of time and space.

Once in awhile, during the remainder of the ocean trip, I experienced a few apprehensive twinges about the coming English-lecture ordeal at the Boston congress.

“Lord,” I prayed, “please let my inspiration be Thyself, and not again the laughter-bombs of the audience!”

The City of Sparta docked near Boston in late September. On the sixth of October I addressed the congress with my maiden speech in America. It was well received; I sighed in relief. The magnanimous secretary of the American Unitarian Association wrote the following comment in a published account 4 of the congress proceedings:

“Swami Yogananda, delegate from the Brahmacharya Ashram of Ranchi, India, brought the greetings of his Association to the Congress. In fluent English and a forcible delivery he gave an address of a philosophical character on ‘The Science of Religion,’ which has been printed in pamphlet form for a wider distribution. Religion, he maintained, is universal and it is one. We cannot possibly universalize particular customs and convictions, but the common element in religion can be universalized, and we can ask all alike to follow and obey it.”

Due to Father’s generous check, I was able to remain in America after the congress was over. Four happy years were spent in humble circumstances in Boston. I gave public lectures, taught classes, and wrote a book of poems, Songs of the Soul, with a preface by Dr. Frederick B. Robinson, president of the College of the City of New York.5

Starting a transcontinental tour in the summer of 1924, I spoke before thousands in the principal cities, ending my western trip with a vacation in the beautiful Alaskan north.

With the help of large-hearted students, by the end of 1925 I had established an American headquarters on the Mount Washington Estates in Los Angeles. The building is the one I had seen years before in my vision at Kashmir. I hastened to send Sri Yukteswar pictures of these distant American activities. He replied with a postcard in Bengali, which I here translate:

I have found the great heart of America expressed in the wondrous lines by Emma Lazarus, carved at the base of the Statue of Liberty, the “Mother of Exiles”:

“While I was conducting experiments to make ‘spineless’ cacti,” he continued, “I often talked to the plants to create a vibration of love. ‘You have nothing to fear,’ I would tell them. ‘You don’t need your defensive thorns. I will protect you.’ Gradually the useful plant of the desert emerged in a thornless variety.”

I was charmed at this miracle. “Please, dear Luther, give me a few cacti leaves to plant in my garden at Mount Washington.”

A workman standing near-by started to strip off some leaves; Burbank prevented him.

“I myself will pluck them for the swami.” He handed me three leaves, which later I planted, rejoicing as they grew to huge estate.

The great horticulturist told me that his first notable triumph was the large potato, now known by his name. With the indefatigability of genius, he went on to present the world with hundreds of crossed improvements on nature—his new Burbank varieties of tomato, corn, squash, cherries, plums, nectarines, berries, poppies, lilies, roses.

I focused my camera as Luther led me before the famous walnut tree by which he had proved that natural evolution can be telescopically hastened.

“In only sixteen years,” he said, “this walnut tree reached a state of abundant nut production to which an unaided nature would have brought the tree in twice that time.”

Burbank’s little adopted daughter came romping with her dog into the garden.

“She is my human plant.” Luther waved to her affectionately. “I see humanity now as one vast plant, needing for its highest fulfillments only love, the natural blessings of the great outdoors, and intelligent crossing and selection. In the span of my own lifetime I have observed such wondrous progress in plant evolution that I look forward optimistically to a healthy, happy world as soon as its children are taught the principles of simple and rational living. We must return to nature and nature’s God.”

“Luther, you would delight in my Ranchi school, with its outdoor classes, and atmosphere of joy and simplicity.”

My words touched the chord closest to Burbank’s heart—child education. He plied me with questions, interest gleaming from his deep, serene eyes.

“Swamiji,” he said finally, “schools like yours are the only hope of a future millennium. I am in revolt against the educational systems of our time, severed from nature and stifling of all individuality. I am with you heart and soul in your practical ideals of education.”

As I was taking leave of the gentle sage, he autographed a small volume and presented it to me.1

“Here is my book on The Training of the Human Plant,” 2 he said. “New types of training are needed—fearless experiments. At times the most daring trials have succeeded in bringing out the best in fruits and flowers. Educational innovations for children should likewise become more numerous, more courageous.”

I read his little book that night with intense interest. His eye envisioning a glorious future for the race, he wrote: “The most stubborn living thing in this world, the most difficult to swerve, is a plant once fixed in certain habits. . . . Remember that this plant has preserved its individuality all through the ages; perhaps it is one which can be traced backward through eons of time in the very rocks themselves, never having varied to any great extent in all these vast periods. Do you suppose, after all these ages of repetition, the plant does not become possessed of a will, if you so choose to call it, of unparalleled tenacity? Indeed, there are plants, like certain of the palms, so persistent that no human power has yet been able to change them. The human will is a weak thing beside the will of a plant. But see how this whole plant’s lifelong stubbornness is broken simply by blending a new life with it, making, by crossing, a complete and powerful change in its life. Then when the break comes, fix it by these generations of patient supervision and selection, and the new plant sets out upon its new way never again to return to the old, its tenacious will broken and changed at last.

“When it comes to so sensitive and pliable a thing as the nature of a child, the problem becomes vastly easier.”

Magnetically drawn to this great American, I visited him again and again. One morning I arrived at the same time as the postman, who deposited in Burbank’s study about a thousand letters. Horticulturists wrote him from all parts of the world.

“Swamiji, your presence is just the excuse I need to get out into the garden,” Luther said gaily. He opened a large desk-drawer containing hundreds of travel folders.

“See,” he said, “this is how I do my traveling. Tied down by my plants and correspondence, I satisfy my desire for foreign lands by a glance now and then at these pictures.”

My car was standing before his gate; Luther and I drove along the streets of the little town, its gardens bright with his own varieties of Santa Rosa, Peachblow, and Burbank roses.

“My friend Henry Ford and I both believe in the ancient theory of reincarnation,” Luther told me. “It sheds light on aspects of life otherwise inexplicable. Memory is not a test of truth; just because man fails to remember his past lives does not prove he never had them. Memory is blank concerning his womb-life and infancy, too; but he probably passed through them!” He chuckled.

The great scientist had received Kriya initiation during one of my earlier visits. “I practice the technique devoutly, Swamiji,” he said. After many thoughtful questions to me about various aspects of yoga, Luther remarked slowly:

“The East indeed possesses immense hoards of knowledge which the West has scarcely begun to explore.”

Intimate communion with nature, who unlocked to him many of her jealously guarded secrets, had given Burbank a boundless spiritual reverence.

“Sometimes I feel very close to the Infinite Power,” he confided shyly. His sensitive, beautifully modeled face lit with his memories. “Then I have been able to heal sick persons around me, as well as many ailing plants.”

He told me of his mother, a sincere Christian. “Many times after her death,” Luther said, “I have been blessed by her appearance in visions; she has spoken to me.”

We drove back reluctantly toward his home and those waiting thousand letters.

“Luther,” I remarked, “next month I am starting a magazine to present the truth-offerings of East and West. Please help me decide on a good name for the journal.”

We discussed titles for awhile, and finally agreed on East-West. After we had reentered his study, Burbank gave me an article he had written on “Science and Civilization.”

“This will go in the first issue of East-West,” I said gratefully.

As our friendship grew deeper, I called Burbank my “American saint.” “Behold a man,” I quoted, “in whom there is no guile!” His heart was fathomlessly deep, long acquainted with humility, patience, sacrifice. His little home amidst the roses was austerely simple; he knew the worthlessness of luxury, the joy of few possessions. The modesty with which he wore his scientific fame repeatedly reminded me of the trees that bend low with the burden of ripening fruits; it is the barren tree that lifts its head high in an empty boast.

I was in New York when, in 1926, my dear friend passed away. In tears I thought, “Oh, I would gladly walk all the way from here to Santa Rosa for one more glimpse of him!” Locking myself away from secretaries and visitors, I spent the next twenty-four hours in seclusion.

The following day I conducted a Vedic memorial rite around a large picture of Luther. A group of my American students, garbed in Hindu ceremonial clothes, chanted the ancient hymns as an offering was made of flowers, water, and fire—symbols of the bodily elements and their release in the Infinite Source.

Though the form of Burbank lies in Santa Rosa under a Lebanon cedar that he planted years ago in his garden, his soul is enshrined for me in every wide-eyed flower that blooms by the wayside. Withdrawn for a time into the spacious spirit of nature, is that not Luther whispering in her winds, walking her dawns?

His name has now passed into the heritage of common speech. Listing “burbank” as a transitive verb, Webster’s New International Dictionary defines it: “To cross or graft (a plant). Hence, figuratively, to improve (anything, as a process or institution) by selecting good features and rejecting bad, or by adding good features.”

“Beloved Burbank,” I cried after reading the definition, “your very name is now a synonym for goodness!”

Sri Yukteswar’s voice sounded startlingly in my inner ear as I sat in meditation at my Mt. Washington headquarters. Traversing ten thousand miles in the twinkling of an eye, his message penetrated my being like a flash of lightning.

Fifteen years! Yes, I realized, now it is 1935; I have spent fifteen years in spreading my guru’s teachings in America. Now he recalls me.

That afternoon I recounted my experience to a visiting disciple. His spiritual development under Kriya Yoga was so remarkable that I often called him “saint,” remembering Babaji’s prophecy that America too would produce men and women of divine realization through the ancient yogic path.

This disciple and a number of others generously insisted on making a donation for my travels. The financial problem thus solved, I made arrangements to sail, via Europe, for India. Busy weeks of preparations at Mount Washington! In March, 1935 I had the Self-Realization Fellowship chartered under the laws of the State of California as a non-profit corporation. To this educational institution go all public donations as well as the revenue from the sale of my books, magazine, written courses, class tuition, and every other source of income.

“I shall be back,” I told my students. “Never shall I forget America.”

At a farewell banquet given to me in Los Angeles by loving friends, I looked long at their faces and thought gratefully, “Lord, he who remembers Thee as the Sole Giver will never lack the sweetness of friendship among mortals.”

I sailed from New York on June 9, 1935 1 in the Europa. Two students accompanied me: my secretary, Mr. C. Richard Wright, and an elderly lady from Cincinnati, Miss Ettie Bletch. We enjoyed the days of ocean peace, a welcome contrast to the past hurried weeks. Our period of leisure was short-lived; the speed of modern boats has some regrettable features!

Like any other group of inquisitive tourists, we walked around the huge and ancient city of London. The following day I was invited to address a large meeting in Caxton Hall, at which I was introduced to the London audience by Sir Francis Younghusband. Our party spent a pleasant day as guests of Sir Harry Lauder at his estate in Scotland. We soon crossed the English Channel to the continent, for I wanted to make a special pilgrimage to Bavaria. This would be my only chance, I felt, to visit the great Catholic mystic, Therese Neumann of Konnersreuth.

Years earlier I had read an amazing account of Therese. Information given in the article was as follows:

Therese’s little cottage, clean and neat, with geraniums blooming by a primitive well, was alas! silently closed. The neighbors, and even the village postman who passed by, could give us no information. Rain began to fall; my companions suggested that we leave.

“No,” I said stubbornly, “I will stay here until I find some clue leading to Therese.”

Two hours later we were still sitting in our car amidst the dismal rain. “Lord,” I sighed complainingly, “why didst Thou lead me here if she has disappeared?”

An English-speaking man halted beside us, politely offering his aid.

“I don’t know for certain where Therese is,” he said, “but she often visits at the home of Professor Wurz, a seminary master of Eichstatt, eighty miles from here.”

The following morning our party motored to the quiet village of Eichstatt, narrowly lined with cobblestoned streets. Dr. Wurz greeted us cordially at his home; “Yes, Therese is here.” He sent her word of the visitors. A messenger soon appeared with her reply.

“Though the bishop has asked me to see no one without his permission, I will receive the man of God from India.”

Deeply touched at these words, I followed Dr. Wurz upstairs to the sitting room. Therese entered immediately, radiating an aura of peace and joy. She wore a black gown and spotless white head dress. Although her age was thirty-seven at this time, she seemed much younger, possessing indeed a childlike freshness and charm. Healthy, well-formed, rosy-cheeked, and cheerful, this is the saint that does not eat!

Therese greeted me with a very gentle handshaking. We both beamed in silent communion, each knowing the other to be a lover of God.

Dr. Wurz kindly offered to serve as interpreter. As we seated ourselves, I noticed that Therese was glancing at me with naive curiosity; evidently Hindus had been rare in Bavaria.

“Don’t you eat anything?” I wanted to hear the answer from her own lips.

“No, except a consecrated rice-flour wafer, once every morning at six o’clock.”

“How large is the wafer?”

“It is paper-thin, the size of a small coin.” She added, “I take it for sacramental reasons; if it is unconsecrated, I am unable to swallow it.”

“Certainly you could not have lived on that, for twelve whole years?”

“I live by God’s light.” How simple her reply, how Einsteinian!

“I see you realize that energy flows to your body from the ether, sun, and air.”

A swift smile broke over her face. “I am so happy to know you understand how I live.”

“Your sacred life is a daily demonstration of the truth uttered by Christ: ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God.’” 3

Again she showed joy at my explanation. “It is indeed so. One of the reasons I am here on earth today is to prove that man can live by God’s invisible light, and not by food only.”

“Can you teach others how to live without food?”

She appeared a trifle shocked. “I cannot do that; God does not wish it.”

As my gaze fell on her strong, graceful hands, Therese showed me a little, square, freshly healed wound on each of her palms. On the back of each hand, she pointed out a smaller, crescent-shaped wound, freshly healed. Each wound went straight through the hand. The sight brought to my mind distinct recollection of the large square iron nails with crescent-tipped ends, still used in the Orient, but which I do not recall having seen in the West.

The saint told me something of her weekly trances. “As a helpless onlooker, I observe the whole Passion of Christ.” Each week, from Thursday midnight until Friday afternoon at one o’clock, her wounds open and bleed; she loses ten pounds of her ordinary 121-pound weight. Suffering intensely in her sympathetic love, Therese yet looks forward joyously to these weekly visions of her Lord.

I realized at once that her strange life is intended by God to reassure all Christians of the historical authenticity of Jesus’ life and crucifixion as recorded in the New Testament, and to dramatically display the ever-living bond between the Galilean Master and his devotees.

Professor Wurz related some of his experiences with the saint.

“Several of us, including Therese, often travel for days on sight-seeing trips throughout Germany,” he told me. “It is a striking contrast—while we have three meals a day, Therese eats nothing. She remains as fresh as a rose, untouched by the fatigue which the trips cause us. As we grow hungry and hunt for wayside inns, she laughs merrily.”

The professor added some interesting physiological details: “Because Therese takes no food, her stomach has shrunk. She has no excretions, but her perspiration glands function; her skin is always soft and firm.”

At the time of parting, I expressed to Therese my desire to be present at her trance.

“Yes, please come to Konnersreuth next Friday,” she said graciously. “The bishop will give you a permit. I am very happy you sought me out in Eichstatt.”

Therese shook hands gently, many times, and walked with our party to the gate. Mr. Wright turned on the automobile radio; the saint examined it with little enthusiastic chuckles. Such a large crowd of youngsters gathered that Therese retreated into the house. We saw her at a window, where she peered at us, childlike, waving her hand.

From a conversation the next day with two of Therese’s brothers,

very kind and amiable, we learned that the saint sleeps only one or two

hours at night. In spite of the many wounds in her body, she is active

and full of energy. She loves birds, looks after an aquarium of fish,

and works often in her garden. Her correspondence is large; Catholic

devotees write her for prayers and healing blessings. Many seekers have

been cured through her of serious diseases.

Her brother Ferdinand, about twenty-three, explained that Therese has the power, through prayer, of working out on her own body the ailments of others. The saint’s abstinence from food dates from a time when she prayed that the throat disease of a young man of her parish, then preparing to enter holy orders, be transferred to her own throat.

On Thursday afternoon our party drove to the home of the bishop, who looked at my flowing locks with some surprise. He readily wrote out the necessary permit. There was no fee; the rule made by the Church is simply to protect Therese from the onrush of casual tourists, who in previous years had flocked on Fridays by the thousands.

We arrived Friday morning about nine-thirty in Konnersreuth. I noticed that Therese’s little cottage possesses a special glass-roofed section to afford her plenty of light. We were glad to see the doors no longer closed, but wide-open in hospitable cheer. There was a line of about twenty visitors, armed with their permits. Many had come from great distances to view the mystic trance.

Therese had passed my first test at the professor’s house by her intuitive knowledge that I wanted to see her for spiritual reasons, and not just to satisfy a passing curiosity.

My second test was connected with the fact that, just before I went upstairs to her room, I put myself into a yogic trance state in order to be one with her in telepathic and televisic rapport. I entered her chamber, filled with visitors; she was lying in a white robe on the bed. With Mr. Wright following closely behind me, I halted just inside the threshold, awestruck at a strange and most frightful spectacle.

Blood flowed thinly and continuously in an inch-wide stream from Therese’s lower eyelids. Her gaze was focused upward on the spiritual eye within the central forehead. The cloth wrapped around her head was drenched in blood from the stigmata wounds of the crown of thorns. The white garment was redly splotched over her heart from the wound in her side at the spot where Christ’s body, long ages ago, had suffered the final indignity of the soldier’s spear-thrust.

Therese’s hands were extended in a gesture maternal, pleading; her face wore an expression both tortured and divine. She appeared thinner, changed in many subtle as well as outward ways. Murmuring words in a foreign tongue, she spoke with slightly quivering lips to persons visible before her inner sight.

As I was in attunement with her, I began to see the scenes of her vision. She was watching Jesus as he carried the cross amidst the jeering multitude.4 Suddenly she lifted her head in consternation: the Lord had fallen under the cruel weight. The vision disappeared. In the exhaustion of fervid pity, Therese sank heavily against her pillow.

At this moment I heard a loud thud behind me. Turning my head for a second, I saw two men carrying out a prostrate body. But because I was coming out of the deep superconscious state, I did not immediately recognize the fallen person. Again I fixed my eyes on Therese’s face, deathly pale under the rivulets of blood, but now calm, radiating purity and holiness. I glanced behind me later and saw Mr. Wright standing with his hand against his cheek, from which blood was trickling.

“Dick,” I inquired anxiously, “were you the one who fell?”

“Yes, I fainted at the terrifying spectacle.”

“Well,” I said consolingly, “you are brave to return and look upon the sight again.”

Remembering the patiently waiting line of pilgrims, Mr. Wright and I silently bade farewell to Therese and left her sacred presence.5

The following day our little group motored south, thankful that we were not dependent on trains, but could stop the Ford wherever we chose throughout the countryside. We enjoyed every minute of a tour through Germany, Holland, France, and the Swiss Alps. In Italy we made a special trip to Assisi to honor the apostle of humility, St. Francis. The European tour ended in Greece, where we viewed the Athenian temples, and saw the prison in which the gentle Socrates 6 had drunk his death potion. One is filled with admiration for the artistry with which the Greeks have everywhere wrought their very fancies in alabaster.

We took ship over the sunny Mediterranean, disembarking at Palestine. Wandering day after day over the Holy Land, I was more than ever convinced of the value of pilgrimage. The spirit of Christ is all-pervasive in Palestine; I walked reverently by his side at Bethlehem, Gethsemane, Calvary, the holy Mount of Olives, and by the River Jordan and the Sea of Galilee.

Our little party visited the Birth Manger, Joseph’s carpenter shop, the tomb of Lazarus, the house of Martha and Mary, the hall of the Last Supper. Antiquity unfolded; scene by scene, I saw the divine drama that Christ once played for the ages.

On to Egypt, with its modern Cairo and ancient pyramids. Then a boat down the narrow Red Sea, over the vasty Arabian Sea; lo, India!

Bombay was a city new to me; I found it energetically modern, with many innovations from the West. Palms line the spacious boulevards; magnificent state structures vie for interest with ancient temples. Very little time was given to sight-seeing, however; I was impatient, eager to see my beloved guru and other dear ones. Consigning the Ford to a baggage car, our party was soon speeding eastward by train toward Calcutta.1

Our arrival at Howrah Station found such an immense crowd assembled to greet us that for awhile we were unable to dismount from the train. The young Maharaja of Kasimbazar and my brother Bishnu headed the reception committee; I was unprepared for the warmth and magnitude of our welcome.

Preceded by a line of automobiles and motorcycles, and amidst the joyous sound of drums and conch shells, Miss Bletch, Mr. Wright, and myself, flower-garlanded from head to foot, drove slowly to my father’s home.

My aged parent embraced me as one returning from the dead; long we gazed on each other, speechless with joy. Brothers and sisters, uncles, aunts, and cousins, students and friends of years long past were grouped around me, not a dry eye among us. Passed now into the archives of memory, the scene of loving reunion vividly endures, unforgettable in my heart.

As for my meeting with Sri Yukteswar, words fail me; let the following description from my secretary suffice.

“This gift I appreciate indeed!” My guru’s eyes were turned on me with affectionate understanding as he made the unwonted comment. From all the presents, it was the cane that he singled out to display to visitors.

“Master, please permit me to get a new carpet for the sitting room.” I had noticed that Sri Yukteswar’s tiger skin was placed over a torn rug.

“Do so if it pleases you.” My guru’s voice was not enthusiastic. “Behold, my tiger mat is nice and clean; I am monarch in my own little kingdom. Beyond it is the vast world, interested only in externals.”

As he uttered these words I felt the years roll back; once again I am a young disciple, purified in the daily fires of chastisement!

As soon as I could tear myself away from Serampore and Calcutta, I set out, with Mr. Wright, for Ranchi. What a welcome there, a veritable ovation! Tears stood in my eyes as I embraced the selfless teachers who had kept the banner of the school flying during my fifteen years’ absence. The bright faces and happy smiles of the residential and day students were ample testimony to the worth of their many-sided school and yoga training.

Yet, alas! the Ranchi institution was in dire financial difficulties. Sir Manindra Chandra Nundy, the old Maharaja whose Kasimbazar Palace had been converted into the central school building, and who had made many princely donations was now dead. Many free, benevolent features of the school were now seriously endangered for lack of sufficient public support.

I had not spent years in America without learning some of its practical wisdom, its undaunted spirit before obstacles. For one week I remained in Ranchi, wrestling with critical problems. Then came interviews in Calcutta with prominent leaders and educators, a long talk with the young Maharaja of Kasimbazar, a financial appeal to my father, and lo! the shaky foundations of Ranchi began to be righted. Many donations including one huge check arrived in the nick of time from my American students.

Within a few months after my arrival in India, I had the joy of seeing the Ranchi school legally incorporated. My lifelong dream of a permanently endowed yoga educational center stood fulfilled. That vision had guided me in the humble beginnings in 1917 with a group of seven boys.

In the decade since 1935, Ranchi has enlarged its scope far beyond the boys’ school. Widespread humanitarian activities are now carried on there in the Shyama Charan Lahiri Mahasaya Mission.

The school, or Yogoda Sat-Sanga Brahmacharya Vidyalaya, conducts outdoor classes in grammar and high school subjects. The residential students and day scholars also receive vocational training of some kind. The boys themselves regulate most of their activities through autonomous committees. Very early in my career as an educator I discovered that boys who impishly delight in outwitting a teacher will cheerfully accept disciplinary rules that are set by their fellow students. Never a model pupil myself, I had a ready sympathy for all boyish pranks and problems.

Sports and games are encouraged; the fields resound with hockey and football practice. Ranchi students often win the cup at competitive events. The outdoor gymnasium is known far and wide. Muscle recharging through will power is the Yogoda feature: mental direction of life energy to any part of the body. The boys are also taught asanas (postures), sword and lathi (stick) play, and jujitsu. The Yogoda Health Exhibitions at the Ranchi Vidyalaya have been attended by thousands.

Instruction in primary subjects is given in Hindi to the Kols, Santals, and Mundas, aboriginal tribes of the province. Classes for girls only have been organized in near-by villages.

The unique feature at Ranchi is the initiation into Kriya Yoga. The boys daily practice their spiritual exercises, engage in Gita chanting, and are taught by precept and example the virtues of simplicity, self-sacrifice, honor, and truth. Evil is pointed out to them as being that which produces misery; good as those actions which result in true happiness. Evil may be compared to poisoned honey, tempting but laden with death.

Overcoming restlessness of body and mind by concentration techniques has achieved astonishing results: it is no novelty at Ranchi to see an appealing little figure, aged nine or ten years, sitting for an hour or more in unbroken poise, the unwinking gaze directed to the spiritual eye. Often the picture of these Ranchi students has returned to my mind, as I observed collegians over the world who are hardly able to sit still through one class period.4

Ranchi lies 2000 feet above sea level; the climate is mild and equable. The twenty-five acre site, by a large bathing pond, includes one of the finest orchards in India—five hundred fruit trees—mango, guava, litchi, jackfruit, date. The boys grow their own vegetables, and spin at their charkas.

A guest house is hospitably open for Western visitors. The Ranchi library contains numerous magazines, and about a thousand volumes in English and Bengali, donations from the West and the East. There is a collection of the scriptures of the world. A well-classified museum displays archeological, geological, and anthropological exhibits; trophies, to a great extent, of my wanderings over the Lord’s varied earth.

The charitable hospital and dispensary of the Lahiri Mahasaya Mission, with many outdoor branches in distant villages, have already ministered to 150,000 of India’s poor. The Ranchi students are trained in first aid, and have given praiseworthy service to their province at tragic times of flood or famine.

In the orchard stands a Shiva temple, with a statue of the blessed master, Lahiri Mahasaya. Daily prayers and scripture classes are held in the garden under the mango bowers.

Branch high schools, with the residential and yoga features of Ranchi, have been opened and are now flourishing. These are the Yogoda Sat-Sanga Vidyapith (School) for Boys, at Lakshmanpur in Bihar; and the Yogoda Sat-Sanga High School and hermitage at Ejmalichak in Midnapore.

A stately Yogoda Math was dedicated in 1939 at Dakshineswar, directly on the Ganges. Only a few miles north of Calcutta, the new hermitage affords a haven of peace for city dwellers. Suitable accommodations are available for Western guests, and particularly for those seekers who are intensely dedicating their lives to spiritual realization. The activities of the Yogoda Math include a fortnightly mailing of Self-Realization Fellowship teachings to students in various parts of India.

It is needless to say that all these educational and humanitarian activities have required the self-sacrificing service and devotion of many teachers and workers. I do not list their names here, because they are so numerous; but in my heart each one has a lustrous niche. Inspired by the ideals of Lahiri Mahasaya, these teachers have abandoned promising worldly goals to serve humbly, to give greatly.

Mr. Wright formed many fast friendships with Ranchi boys; clad in a simple dhoti, he lived for awhile among them. At Ranchi, Calcutta, Serampore, everywhere he went, my secretary, who has a vivid gift of description, hauled out his travel diary to record his adventures. One evening I asked him a question.

“Dick, what is your impression of India?”

“Peace,” he said thoughtfully. “The racial aura is peace.”

At my words Mr. Wright looked startled, then pleased. We had just left the beautiful Chamundi Temple in the hills overlooking Mysore in southern India. There we had bowed before the gold and silver altars of the Goddess Chamundi, patron deity of the family of the reigning maharaja.

“As a souvenir of the unique honor,” Mr. Wright said, carefully stowing away a few blessed rose petals, “I will always preserve this flower, sprinkled by the priest with rose water.”

My companion and I 1 were spending the month of November, 1935, as guests of the State of Mysore. The Maharaja, H.H. Sri Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV, is a model prince with intelligent devotion to his people. A pious Hindu, the Maharaja has empowered a Mohammedan, the able Mirza Ismail, as his Dewan or Premier. Popular representation is given to the seven million inhabitants of Mysore in both an Assembly and a Legislative Council.

The heir to the Maharaja, H.H. the Yuvaraja, Sir Sri Krishna Narasingharaj Wadiyar, had invited my secretary and me to visit his enlightened and progressive realm. During the past fortnight I had addressed thousands of Mysore citizens and students, at the Town Hall, the Maharajah’s College, the University Medical School; and three mass meetings in Bangalore, at the National High School, the Intermediate College, and the Chetty Town Hall where over three thousand persons had assembled. Whether the eager listeners had been able to credit the glowing picture I drew of America, I know not; but the applause had always been loudest when I spoke of the mutual benefits that could flow from exchange of the best features in East and West.

Mr. Wright and I were now relaxing in the tropical peace. His travel diary gives the following account of his impressions of Mysore:

The most breath-taking display of architecture, sculpture, and painting in all India is found at Hyderabad in the ancient rock-sculptured caves of Ellora and Ajanta. The Kailasa at Ellora, a huge monolithic temple, possesses carved figures of gods, men, and beasts in the stupendous proportions of a Michelangelo. Ajanta is the site of five cathedrals and twenty-five monasteries, all rock excavations maintained by tremendous frescoed pillars on which artists and sculptors have immortalized their genius.

Hyderabad City is graced by the Osmania University and by the imposing Mecca Masjid Mosque, where ten thousand Mohammedans may assemble for prayer.

Mysore State too is a scenic wonderland, three thousand feet above sea level, abounding in dense tropical forests, the home of wild elephants, bison, bears, panthers, and tigers. Its two chief cities, Bangalore and Mysore, are clean, attractive, with many parks and public gardens.

Hindu architecture and sculpture achieved their highest perfection in Mysore under the patronage of Hindu kings from the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries. The temple at Belur, an eleventh-century masterpiece completed during the reign of King Vishnuvardhana, is unsurpassed in the world for its delicacy of detail and exuberant imagery.

The rock pillars found in northern Mysore date from the third century B.C., illuminating the memory of King Asoka. He succeeded to the throne of the Maurya dynasty then prevailing; his empire included nearly all of modern India, Afghanistan, and Baluchistan. This illustrious emperor, considered even by Western historians to have been an incomparable ruler, has left the following wisdom on a rock memorial: